The End of an Academic Dream (opinion)

When I look back on the final months of my Ph.D. in comparative literature at the University of Edinburgh, I remember a strange duality: the thrill of intellectual accomplishment and the gnawing dread of what would come next. I had spent years immersed in research, convinced that my work examining gendered urban spaces in Turkish literature mattered not just to me, but to the world. I believed, perhaps naively, that universities and other academics in the humanities would recognize my passion and reward my dedication. Like so many others, I had internalized the myth of the noble, wandering academic, of the scholar who sacrifices comfort and security for the life of the mind, who hops from conference to conference, who finds meaning in precarity and purpose in poverty. This narrative became my identity, even as I quietly ignored its cost.

Looking back, I realize how seductive and insidious this myth truly is. The image of the ever-mobile scholar who is untethered, devoted and always in pursuit of the next idea has a certain romance, but it also masks the profound instability that underlies academic life today. The expectation that we must be willing to uproot ourselves repeatedly, to accept underpaid adjunct roles in distant cities, to live out of suitcases for years on end, is often framed as a credential. But beneath this veneer of adventure lies exhaustion, loneliness and a growing sense of alienation. The myth tells us that uncertainty is evidence of our devotion—but in reality, it can be deeply wounding. It asks us to pay a price: to accept uncertainty as normal, to treat exhaustion as a qualification and to ignore the toll it takes on our relationships, our sense of belonging and our mental health.

As the end of my Ph.D. approached, this romantic haze lifted. The job market was not just competitive: It was indifferent. Each application painstakingly tailored, each cover letter a miniature essay: Everything felt like a hopeful message in a bottle tossed into a brutal and unknown sea. The silence that followed was deafening. When responses did come, they were polite rejections, often generic, sometimes apologetic, but always final. My applications went cold. Outside the rarefied world of academia, my expertise in gendered urban spaces in Turkish literature was, at best, a curiosity. At worst, it was a liability: “overqualified,” “not the right fit,” “too specialized.” Each rejection chipped away at the confidence I had so carefully constructed during my Ph.D. years. I began to question not only my career choices, but my very identity. If I wasn’t an academic, who was I?

What I hadn’t anticipated was how personal each rejection would feel. The process was not just about jobs, but rather about validation. After years of being told that my work mattered, that my perspective was unique, I was now being told, in so many words, that there was no place for me. I remember the sting of opening yet another rejection email while sitting at home writing yet another cover letter, fighting back tears, feeling exposed and invisible all at once. The academic job market is not just a test of credentials. It is a test of endurance, of self-worth and of how much rejection one can absorb before breaking.

There were nights I lay awake, tormented by the math of survival. The price of a sandwich became a symbol of everything I had lost and everything I feared I would never have. I felt ashamed for wanting more than subsistence, for craving both intellectual fulfillment and financial stability, as if the two were mutually exclusive, as if my dream for a dignified life was a betrayal of the academic ideal. I withdrew from friends and family, unable to explain the strange affliction of watching a lifelong dream dissolve. I told lies about interviews and prospects, desperate to maintain the illusion that I was still on track, still worthy.

Suddenly, the pressure became too much to bear, and I made the decision to leave academia. I grieved this choice that I believed was forced upon me. I felt ashamed for not “making it,” for letting down mentors, for not living up to the expectations I had set for myself and that others had set for me. For years, I had introduced myself as a scholar, a researcher, a future professor. Now, I struggled to answer the simple question “What do you do?”

Friends outside academia couldn’t understand the stakes, while those within it were either too busy navigating their own careers or unwilling to acknowledge the possibility of failure. Yet, in that darkness, I also found a strange kind of freedom. With the academic path closed, I could ask myself, perhaps for the first time in years, “What do I want? What do I value? What kind of life do I want to build?”

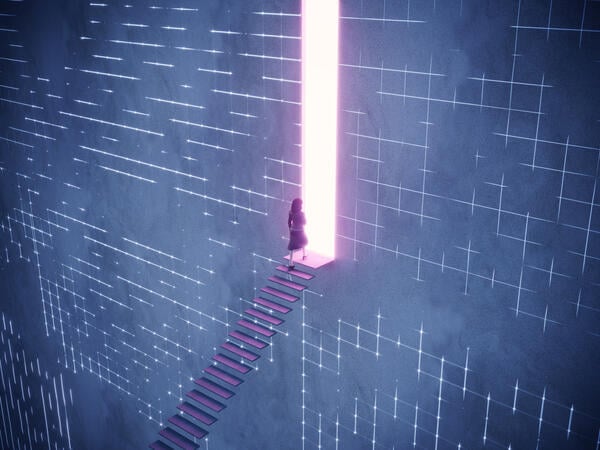

It was in this liminal space between loss and possibility that I began to see the chance to create a new self. The grief was real, but so was the relief. I no longer had to pretzel myself to fit a system that had no place for me. I could begin, tentatively, to imagine a life where my worth wasn’t measured by publications or fellowships, but by my own sense of meaning and connection.

Navigating the job market post-Ph.D. was a lesson in humility and reinvention. I learned to reframe my experience: Research became “project management,” teaching became “public speaking” and “training,” conference presentations turned into “stakeholder engagement.” I rewrote my story, sometimes daily, in the form of cover letters and résumés that tried to translate my academic experience into something legible to the outside world.

The process was humbling, even humiliating at times. I sent applications everywhere: to charter schools, to media outlets, to tech start-ups. I learned to pitch myself as a curriculum designer, an editor, a content strategist. I learned to accept rejection as a fact of life, not a reflection of my intelligence. I practiced new scripts for interviews, hoping to bridge the gap between my world and theirs. There were awkward moments that I tripped over, such as explaining why I spent years studying Turkish literature, or why I left academia at all. Yet, there were also moments of small triumphs. The first time a hiring manager told me, “We’re impressed by your background,” I felt a surge of pride.

Eventually, I landed a contract role with a technology company, drawing on skills I had developed in academia but never thought would matter outside it: managing projects, editing complex documents, collaborating across disciplines. The first time I was able to pay my bills comfortably, I wept with relief. These victories were not the ones I had imagined when I started my Ph.D., but they were real, and they mattered.

If I could offer advice to others facing this uncertain landscape, it would be to first allow yourself time to grieve. The end of an academic dream is a real loss, and it deserves to be mourned. But do not let that grief define you. Instead, let it open space for curiosity, for experimentation, for new forms of meaning. Seek out communities beyond academia such as in your city and among friends who have walked similar paths. Find mentors who see your potential, not just your pedigree.

Be creative in how you translate your skills. The world is full of problems that require the very things you have mastered, such as the ability to analyze, to communicate and to see patterns where others see chaos. Don’t be afraid to invent your own job title, or to propose projects that don’t fit neatly into existing boxes. The humanities teach us to imagine alternatives, so use that training to imagine a future for yourself.

And finally, question the myth of the nomadic academic. We are told that meaning comes from sacrifice, that instability is a mark of seriousness, but this is not the only way to live a life of the mind. You deserve stability, community and joy. You can build a life that honors your scholarship and your humanity, one that is rooted, not rootless, and that makes space for both intellectual passion and personal fulfillment.

I am still, in many ways, searching. But I am no longer searching for permission to belong to academia. I am building a life that honors both my scholarship and my humanity. That, I have learned, is the real work of life after the Ph.D.

Source link