Scientific Publishing Industry Faces Federal Scrutiny

Long-standing criticisms of academic publishing are helping to fuel the Trump administration’s attacks on the nation’s scientific enterprise.

For years, some members of the scientific community have raised alarm about research fraud, paper mills, a paucity of qualified peer reviewers and the high cost of academic journal subscriptions and open-access fees. Research also suggests those problems are rooted in academic incentive structures that reward scientists for publishing a high volume of papers in widely cited journals.

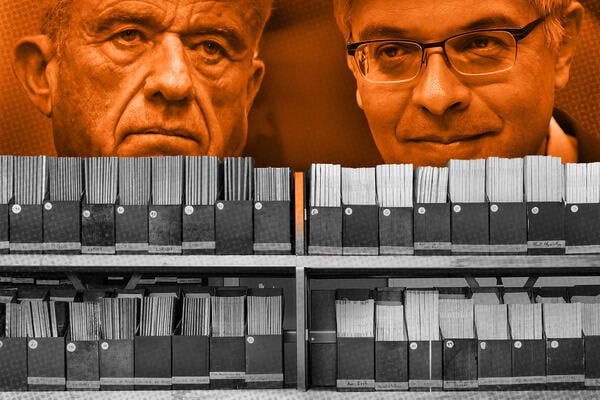

In recent months, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services, and Jayanta Bhattacharya, director of the National Institutes of Health, have taken aim at the scientific publishing industry, changing policies and using their platforms to lodge their own criticisms. They’ve pledged to address concerns about bias, misinformation and access. In August, Bhattacharya wrote in a memo that part of his strategy to rebuild public trust in science will include focusing on “replicable, reproducible, and generalizable research” as “the basis for truth in biomedical science.” The “publish or perish” culture, he added, “favors the promotion of only favorable results, and replication work is little valued or rewarded.”

While numerous experts Inside Higher Ed interviewed said some of the government’s grievances about scientific publishing are real, they’re skeptical that the solutions the HHS and NIH have proposed so far will yield meaningful reforms. And one warned that the Trump administration—which continues to promote misinformation about vaccines, among other things—is exploiting that reality to further its own ideological agenda.

“We all know there are enormous problems facing science and scientific publishing. But a lot of the scientific community is pretending there are no problems,” said Luís A. Nunes Amaral, an engineering professor at Northwestern University who co-authored a paper that identified a surge in research fraud over the past 15 years. “This attitude empowers demagogues to then come and point out issues that are real and recognizable. This gives them some sense of [legitimacy], but in reality they are not trying to improve things; they are trying to destroy them.”

In addition to terminating hundreds of NIH research grants that don’t align with the its ideological views and proposing to cut 40 percent of the NIH’s budget, the Trump administration’s quest to reshape academic publishing could end up giving the government more control over journals that have long acted as the gatekeepers of validated scientific research.

‘Utterly Corrupt’

Even before he became the nation’s top public health official earlier this year, Kennedy characterized multiple top medical journals, including The New England Journal of Medicine and The Lancet, as “utterly corrupt,” saying during his 2024 presidential campaign that he wanted to take legal action against them. Although he hasn’t sued any journals yet, as HHS secretary Kennedy threatened in May to bar government-funded scientists from publishing in those and other journals, claiming that they are controlled by the pharmaceutical industry.

Influence from the pharmaceutical industry is a concern editors of medical journals have also raised. In 2009, Marcia Angell, former editor in chief of NEJM, wrote that researchers’ financial ties to pharmaceutical companies made it “no longer possible to believe much of the clinical research that is published.”

However, in an opinion article STAT published in June, Angell and two other former NEJM editors explained that journals didn’t create the issue, but researchers have come to rely on support from pharmaceutical companies. They noted that journals have taken steps to mitigate industry influence, including requiring authors to disclose ties to relevant companies.

“Kennedy is right that the dependence of medical research on pharmaceutical funding is a problem,” the former editors wrote. “But Kennedy’s actions as head of HHS—including his deep cuts to the National Institutes of Health and targeting of our best medical journals—will make that problem worse.”

Kennedy has also floated the idea of launching an in-house government journal as a solution to rooting out corruption. But Ivan Oransky, a medical researcher and cofounder of Retraction Watch, said that could also raise credibility questions.

“I’m not quite sure what creating a journal accomplishes. It’s just another journal that will have to compete with other journals,” he said. “The other question is, will it be fair and balanced? Will it be interested in what’s true and getting good science out there or only in science that [Kennedy] believes is worthwhile? That’s a real fear given a lot of his pronouncements and what he’s trying to do.”

(Kennedy has espoused numerous unsubstantiated or debunked medical claims, including that vaccines cause autism.)

‘Hot Mess’

While Oransky acknowledged that academic publishing is indeed a “hot mess” that “encourages awful incentives that make it difficult to trust all of the scientific literature,” he said, “Rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic” won’t fix anything.

“The NIH is a major funder of research, so why don’t they change their incentives?” he said. “They could change the peer-review system at the NIH so that nobody privileges citations and high-impact-factor journals.”

Kennedy isn’t the only one who’s questioned the integrity of medical journals.

In April, then-interim U.S. attorney for the District of Columbia Edward R. Martin Jr. sent letters to numerous journals, including The Journal of the American Medical Association and CHEST (a journal published by the American College of Chest Physicians), questioning them about what he called political bias.

And before taking his post, Bhattacharya and Martin Kulldorff, a former Harvard University biostatistician, launched their own journal—The Journal of the Academy of Public Health, which is linked to the right-wing news site RealClearPolitics—as a counter to mainstream journals. During the pandemic, Bhattacharya and Kulldorff co-authored the Great Barrington Declaration, which called on public health officials to scale back stay-at-home recommendations aimed at mitigating the spread of disease and received widespread criticism from NIH officials at the time. Critics worry that the new journal may become a platform for some of the dubious research pushed by the Trump administration.

Political concerns aside, the journal touts that it pays peer reviewers and makes all of its content freely available—policies some science advocates have also called for more journals to implement. In July, the NIH sped up the implementation of a Biden-era policy that requires federally funded researchers to deposit their work into agency-designated public-access repositories, including the NIH-run PubMed Central, immediately upon publication.

But opening access to scientific research won’t be enough to restore public trust in science, said Meagan Phelan, communications director for the Science family of journals.

“If your goal is to restore public trust, you also have to listen to areas of public interest and concern,” she said, noting that the scientific process isn’t always well understood by the general public. “What kinds of things will they do alongside publishing to really listen to public concern and help restore public trust? It’s not as simple as just making this stuff free.”

As NIH director, Bhattacharya has also pledged to rein in the $19 billion for-profit academic publishing industry, which academics, who typically author and peer review articles without compensation, have long criticized as exploitative. In July, the NIH proposed capping the article processing charges (APCs) some journals levy on researchers to make their publications freely available, which can range from hundreds to thousands of dollars.

Bhattacharya has said the move is aimed at both ending the “perverse incentives” enriching the publishing industry and making it “much harder for a small number of scientific elite to say what’s true and false.”

Scientists Need to Lead Reform

While scientists and open-access advocates have also criticized APCs, several say they don’t think the NIH’s plan to implement an artificial cap is a comprehensive enough strategy to reform scientific publishing or academic incentive structures.

“Publishing now is a really complicated system that has a lot of competing, intertwined goals. It’s not easy to change one lever and think it’s going to have the effect that we want,” said Jennifer Trueblood, director of the cognitive science program at Indiana University at Bloomington. “On the surface, capping APCs may make sense to a lot of people. But how would a commercial publisher respond to that? They could easily just shift costs back to libraries and readers.”

And as for reforming the incentive structures tempting some scientists to publish faulty research, the NIH won’t be able to do that alone, either.

“A change needs to be led by scientists,” Trueblood said. “Academic institutions need to rethink how they’re evaluating scientists and making sure that evaluation isn’t feeding into a system that is supporting commercial publishing.”

Source link