Rethinking SAMR in the Age of AI: Why the Model Needs a Second Axis

When the SAMR model was introduced by Ruben Puentedura in the early 2000s, it quickly became one of the most widely used frameworks for talking about technology integration in schools. Its four categories -Substitution, Augmentation, Modification, Redefinition – gave educators simple language to describe how technology changes learning tasks.

At its best, SAMR made something abstract feel concrete. Teachers could point to a lesson and say:

“I’m substituting paper quizzes with digital ones.”

“I’m modifying research by letting students collaborate in a shared doc.”

“I’m redefining storytelling with multimedia tools.”

But as SAMR spread, the field reshaped it. What was originally a descriptive model became prescriptive. Substitution was cast as “entry-level,” Augmentation “better,” and Redefinition the gold standard. SAMR stopped functioning as a tool for reflection and instead became a staircase to ascend.

In the era of AI, that staircase behaves like a Penrose illusion – an infinite climb that doesn’t necessarily lead anywhere. AI can make simple tasks powerful or make advanced tasks hollow. The single-axis interpretation of SAMR simply isn’t enough.

A New Insight Emerging From the Portrait of a Teacher Project

This limitation became clear during a recent meeting of the Advisory Council for The Portrait of a Teacher in the Age of AI, a national research and design initiative led by the non-profit organization Ed3. The project brings together educators, researchers, technologists, district leaders, and policy thinkers to rethink what excellent teaching looks like in an AI-rich world.

A central question emerged:

“Does SAMR need a second axis?”

While reviewing data from our first national survey, where teachers evaluated their use of AI across the SAMR spectrum, we saw a pattern that the original model does not account for. Teachers described Substitution, Augmentation, Modification, and Redefinition in terms of how those actions affected learning, not just what category they belonged to. Some uses strengthened relationships, deepened thinking, or expanded access. Others weakened those very things.

Every level of SAMR showed both a positive and a negative expression.

That observation led to a crucial reframing: SAMR doesn’t just describe what kind of change technology introduces, it also needs to describe whether that change is constructive or destructive.

The Missing Dimension: SAMR Positive and SAMR Negative

Across the survey and the Council’s discussion, the same nuance reappeared: the SAMR level does not determine the quality of practice. The direction of impact does.

Substitution is a clear example.

Replacing repetitive paperwork with AI can free teachers for conferences, feedback, and real human interaction. That’s SAMR positive.

But Substitution can also replace meaningful teacher-student moments with automated scoring that no one reviews, or with chatbot-only communication that eliminates human connection. That’s SAMR negative.

The same duality holds across the model:

- Positive Redefinition: AI enables richer inquiry, real-world projects, multilingual storytelling, and creative expression.

- Negative Redefinition: AI shortcuts struggle, isolate learners, or turn collaboration into parallel conversations with a bot.

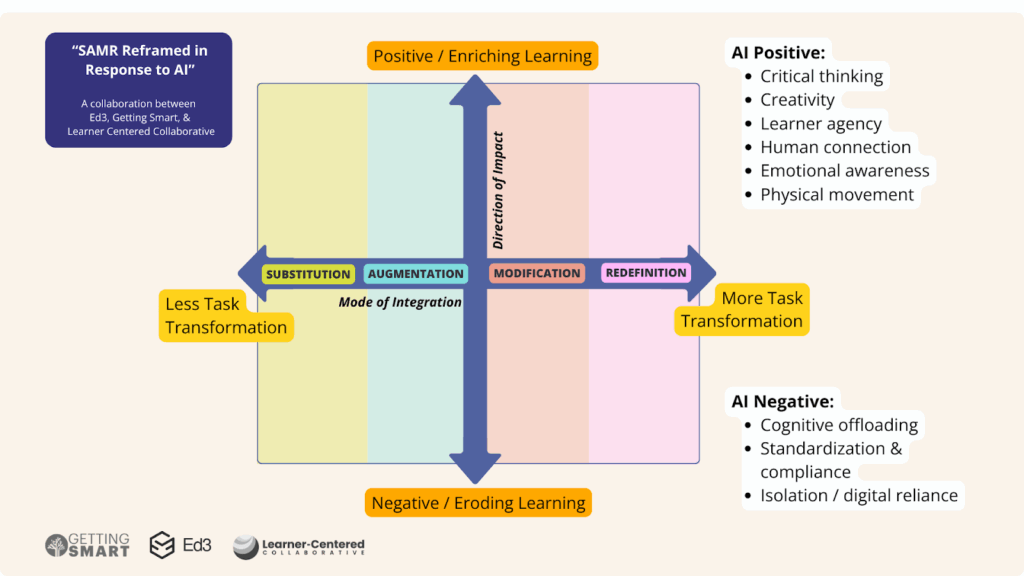

This leads naturally to a reframing of the model itself. Rather than a single ladder, SAMR becomes a two-axis system:

- Axis 1: Mode of integration (Substitution, Augmentation, Modification, Redefinition)

- Axis 2: Direction of impact (Negative ↔ Positive)

Seen this way, SAMR is not a climb from “less innovative” to “more innovative.” It becomes a set of modes, each capable of enriching learning (positive) or eroding learning (negative).

Four nuances emerge from this new perspective:

1. The level doesn’t predict the quality.

The assumption that Substitution is shallow and Redefinition is transformational doesn’t hold. Both can elevate or erode learning depending on how they’re used.

2. Efficiency and erosion can look identical at first glance.

Efficiency becomes positive when it recovers time for presence, attention, and feedback. It becomes negative when it replaces judgment or narrows human interaction.

3. Redefinition can be transformative, or it can empty learning of substance.

AI can help students do work they could never do alone. It can also give them polished products without struggle, inquiry, or iteration.

4. The dividing line is relational, not technological.

Positive uses strengthened connection, feedback, and access. Negative uses distanced teachers from students, encouraged over-reliance, or replaced human insight with automated output.

SAMR’s four levels describe the type of change. The positive-negative axis describes the impact of that change. Only with both can we understand how AI is shaping teaching and learning.

SAMR Isn’t Sequential and Never Was

Another misconception surfaced in the Council’s conversation: SAMR was never meant to be sequential. Teachers don’t follow a predictable path from S → A → M → R.

AI makes this especially clear.

A teacher might begin with Redefinition because simulations or adaptive tutors open possibilities that never existed. Later, they might rely on Substitution to save time generating materials so they can meet individually with students.

Seen this way, SAMR functions as a set of modes, each useful under different instructional conditions.

Once the hierarchy of SAMR collapses, a better set of evaluative questions emerges:

- Does this use of AI deepen human connection or weaken it?

- Does it expand teacher capacity or restrict it?

- Does it open opportunities for students or narrow them?

These questions focus on the direction of impact, not perceived sophistication. Every level of SAMR can be excellent, and every level can be harmful. The distinction lies in whether the practice is progressive or regressive.

The Adoption Curve Connection

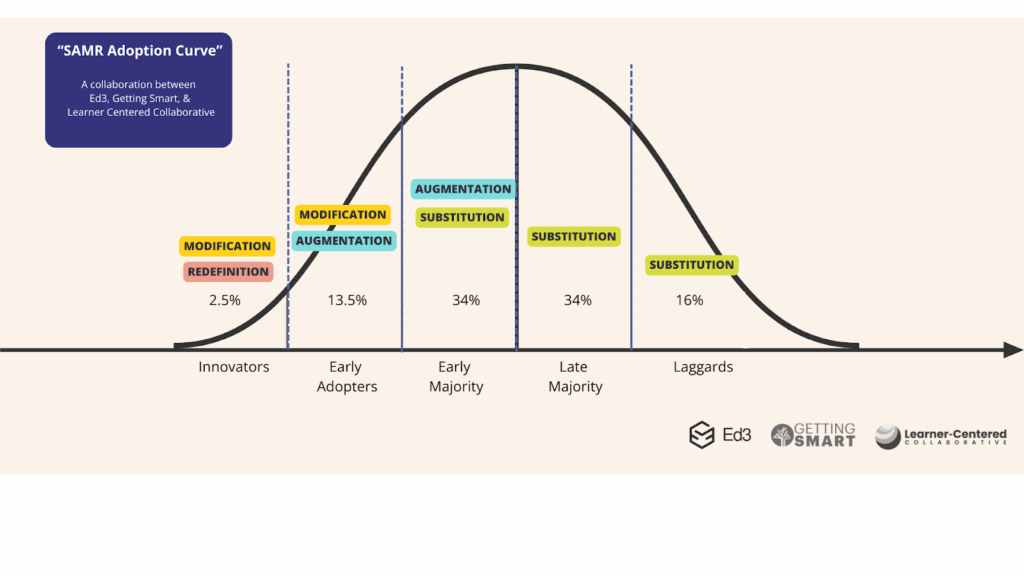

Finally, we concluded that SAMR interacts with the technology adoption cycle.

Early adopters tend to explore Redefinition sooner because they’re comfortable with experimentation. Later adopters often begin with Substitution because it reduces stress and workload, providing an on-ramp that feels safe. This reframing shifts the narrative.

Teachers linger in certain parts of SAMR not because they lack ambition or creativity, but because they’re at different phases of adoption.

Mapping SAMR to the adoption curve helps leaders set realistic expectations and design more effective supports.

Toward a Two-Axis SAMR Model

This updated structure turns SAMR from a ranking tool into a diagnostic one, far better suited to the realities of AI, where efficiency can erode relationships, and advanced tools can either elevate or hollow out learning.

A two-axis SAMR model acknowledges the complexity of teacher practice, respects the diverse contexts educators navigate, and centers human judgment as the defining variable. As AI becomes more embedded in classroom work, the question that matters isn’t “How high on SAMR is this?” but:

“Is this use of AI accelerating or slowing down learning outcomes?”

The questions raised in this article sit at the heart of the Portrait of a Teacher in the Age of AI initiative. If you’re curious about where this research is heading or how you might support or collaborate on the work, we’d welcome your involvement. Check out the project here and join the Brain Trust for regular updates!

Source link