In Ukiah, Eternal Truths Are Saving Young Lives

Ukiah, California is a lot of things at once.

A verdant outpost, equidistant from San Francisco and Oregon — and equally beloved to both sides of our country’s polarized political landscape.

A part of the Emerald Triangle, a three-county grower’s paradise in which marijuana production has made up as much as one-third of the local economy.

A site of genocide against the area’s original inhabitants, the Pomo, an act for which California’s Governor recently apologized.

And a topography that tracks humanity’s stubborn efforts to stake its claim on this place, with single-story strip malls, gas stations, and rivers of concrete fighting to freeze it into prefabricated form, while, unmoving and unmoved, the natural world stands above and around, eternal.

For Kita Grinberg, it’s the beauty that led her here. A Californian by birth, she’d been living and teaching in Oakland, but city life was wearing on her, and she yearned for a deeper immersion in nature. So when a friend told her about an empty cabin on Ukiah’s outskirts, she headed north for a new life, and found a job teaching at the local jail.

It was rewarding work, but in time she heard about a small alternative school just off the main downtown strip, with a family circle of redwood trees in the backyard and a makeshift family of teenagers hoping to reclaim their life stories. “This is the work I feel called to do,” she told me — “to help young people find their gifts, heal, and figure out how the hell to live in this world.”

It felt that way to Kirsten Turner, too. Born in Ukiah, a lifelong educator and single mother with twin teenage boys, Turner had seen the way her hometown had changed over the years. “There are more problems here now than when I was growing up,” she said. “Gangs and fentanyl. The economy of the whole area has changed a lot. This was an oasis for illegal pot growing, and a lot of that money helped seed small businesses here. But then pot got legalized, and we’re still feeling the size of that paradigm shift. A lot of people are struggling.”

Simon Keegan is not one of them, but he is immersed in his hometown city’s struggles nonetheless. “I’ve always been pretty anti-authoritarian,” he confessed. “I knew adults weren’t always right at a very young age. I also know that if you continually ask kids to do something they can’t — particularly ones who are hurting — I can guarantee what their reaction will be. But take the same kid, and ask them to do something within their ability or their strengths, and they’re going to do everything they can to succeed and be helpful.

“That’s what’s so special about this place,” he continued, referring to the school, Big Picture South Valley High School, where he, Kita Grinberg and Kirsten Turner all work. “Schools have created harm over and over again. And it’s hard not to, within the system in which we all still find ourselves.

“We have to allow kids to feel like they’re a part of the team. We all want to be contributing members of a community. That’s why I want to help what’s happening here happen in more places.”

* * *

Big Picture South Valley High School is a continuation school, which means it exists solely for students who have fallen behind on the credits they need to graduate. The earliest someone can enter is 10th grade. And while the big local high school has almost 2000 students, South Valley has just 100.

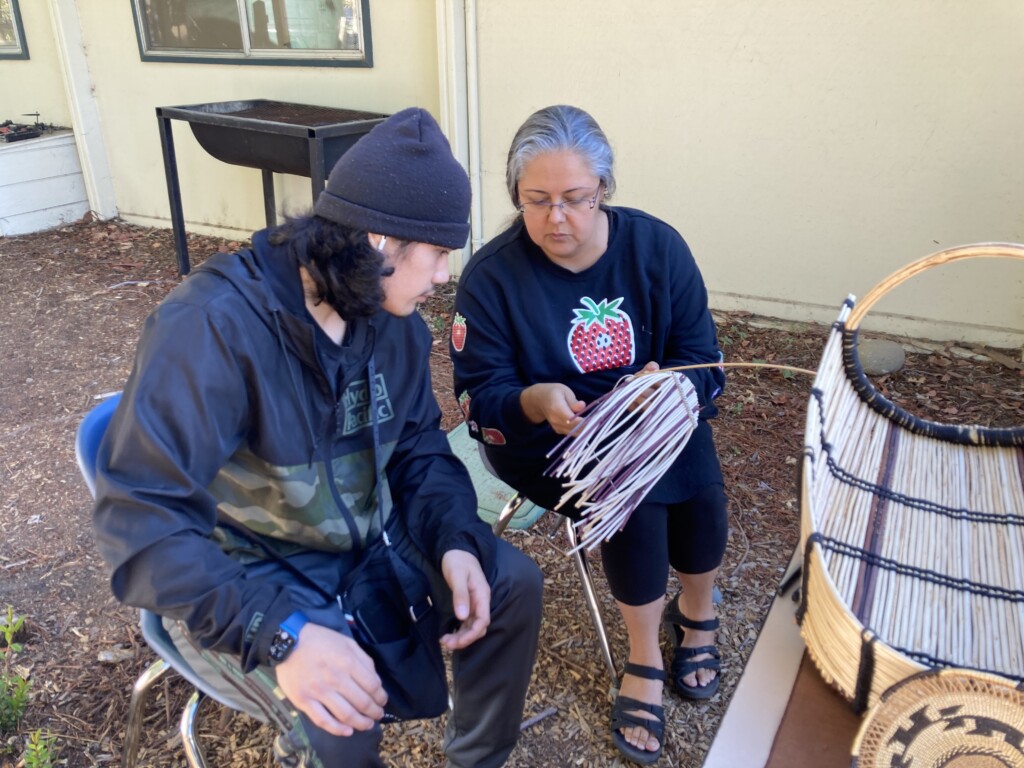

When it was first founded, in 1965, it was known, derogatorily, as the Indian School — and today, as many as one in five students still are. But eight years ago, South Valley decided to join Big Picture Learning, the global network of nearly 300 schools that deploy a very different organizational model.

At Big Picture Learning Schools, the entire learning experience is personalized to each student’s interests, talents and needs. Instead of a whole slate of subject teachers, each student is assigned a single advisor — for the duration of their high school experience — whose job is to know them, support them, and facilitate a steady stream of internships and mentorships that will take young people out of the school building. And last year, in connection with its efforts to expand its community connections, South Valley became one of twelve pilot sites nationwide to explore, with Education Reimagined, what it means to establish a thriving “learner-centered ecosystem,” one that can make the school itself a community-wide place of healing.

“Big Picture and learner-centered ecosystems embody the principles of what we are striving to create here,” Grinberg told me one recent morning, as students made their way to their respective advisories. “We place the emphasis on adults being in service to young people to help them craft their own journeys and uncover their unique brilliance. And to do that, we must bring a disposition towards young people that is fueled by an unwavering commitment to support their growth — as opposed to, say, just a specific content expertise.”

Nearby, Kirsten Turner was arranging the chairs in her room to allow for a morning circle. By design, a third or more of South Valley’s students are new to the school each year, so there was still a fair amount of getting to know each other to be done.

A moment later, her students started to arrive. Most were dressed in shades of black, brown or grey; one young girl arrived with her toddler son in a stroller.

Turner greeted each directly and warmly, and asked each of them to start the day by naming a strength they were bringing to the school, as well as a thing they’d like to experience sometime this year.

“I give good advice,” Blanca begins. “And I want to make new friends.”

“I’m a good listener, too,” Gloria adds. “And I’m excited to meet new people.”

Bernarda, the young mother, is next. Before she begins, Turner translates the directions into Spanish. Bernarda attempts to answer the question while her son squirms and cries on her lap. “I want to learn English this year,” she says softly in Spanish — although that, too, is not her native tongue; it’s Chatino, an indigenous Mesoamerican language spoken by less than 50,000 people worldwide.

Meanwhile, just down the hall, Keegan’s Advisory is listening to a song from Gilberto Gil, Andar Com Fe. It sounds bouncy and light — the sort of sonic misdirection you find in a lot of Bob Marley songs that are, in fact, about systemic oppression. “This music doesn’t sound radical, does it?” he asks the room. “But this guy went to prison for that song during the Brazilian dictatorship. His message was to walk with faith, and to have a clear sense of ourselves and what we believe in. That’s something I want you to be thinking about as you start to work on your ‘Who Am I’ presentations.”

At Big Picture schools, all students are expected to reflect deeply on who they are — and who they aspire to become — and to share those reflections publicly as a way to deepen each person’s capacity to chart their own path through life. “There is a mindset shift required here,” Turner told me later, during a mid-morning break. “In a traditional mindset, the teacher tells you what to learn. But in a school like ours, you decide what you want to learn — which actually requires more work on your part, and a lot more inner reflection.”

After the break, the entire school walks across the street to a nearby room that, unlike any space on campus, is big enough to house them all.

It’s the meeting room for the Ukiah City Council, complete with official-looking swivel chairs and a row of flags at the front. “I already have such a good feeling about our community this year,” Kita begins. “We want to go over a few key things about what makes us different before we get any further into the year.”

Fittingly, for a school that places such a priority on elevating youth voice, students provide the rest of the orientation. “Our school is heavily based on community, if you haven’t figured that out yet,” says a bright-eyed senior named Rowan. “We want people to feel like they belong — because we all want that. You’re here because you didn’t fit in somewhere else before.”

Later that day, I track down Rowan and two of his classmates, fellow seniors Mikey and Marlena, to better understand what this place has meant to them — and why it has been so effective.

“I left my former school to escape the fights and the drinking in the bathrooms, “ explained Mikey. “I guess I’d say I was a doormat for the longest time, just letting people walk all over me. But now I feel like there is something bigger for me to do while I’m here on earth.”

Rowan, wearing a bandana and a long silver chain outside his shirt, speaks next. “I was a try-hard kid. I wanted to get straight A’s and go to Stanford. But halfway through freshman year I started smoking a lot of weed and hanging out at the skatepark. And then sophomore year I didn’t even try. I didn’t want to come here, and even after I did, I kept trying to slack off. But Keegan wouldn’t let me; he started really pushing me. And then he literally took me door to door to find a good internship. I just felt like he was invested in my future as a person.”

Three years later, Rowan is taking eleven credits at the local college, and doing internships for both a local clothier and an ecological restoration organization. “I’m substance clean and I feel more present. I understand my goals and what I want in life. And I feel more grounded in who I am.”

Marlena, who is one of South Valley’s many Indigenous students, told a different story. “From elementary to sixth grade, I was pretty focused. But then I got into a bad relationship that lasted four years — a guy who was just really controlling, and I lost myself. I went downhill fast. But a friend came here our sophomore year, and thought it might be a good place for me, too. And honestly, coming here has changed my life. They helped me find myself again, and now I feel really driven by my own passions, whereas before I didn’t care about anything.”

“Too often,” Mikey jumped in, “we can get stuck in a cycle of just sleepwalking through our own childhood — stumbling through the school day, going home to play video games, going to bed, and then doing it all over again. It’s like being part of a larger system that is literally teaching you how to endure your life while having a soul-crushing job. But what I like about South Valley is it’s basically saying, ‘F–k school the way we have always done it. Learning happens anywhere. You just need to go and find it.”

My day ends sitting in the shade of the school’s redwood trees with Simon Keegan. He is wearing a black t-shirt with a picture of the school’s mascot — a Phoenix (of course) — and still emitting the same smoldering intensity he brought to his advisory conversation five hours earlier.

“This work requires real patience,” he began. “There are ebbs and flows for every kid — and you never know exactly when or if it will all come together and work out. But this is not a gotcha place. It’s growth oriented for everyone. And we don’t get along all the time — but we definitely all respect each other. And the recipe we’re following is as timeless as the beauty of this place:

“Listen to young people. Honor what they need and want. And partner with them by placing them at the center of their own journey.”

This article is part of a series highlighting sites from Education Reimagined’s Learner-Centered Ecosystem Lab. In collaboration with writer, filmmaker, and global design consultant Sam Chaltain, Education Reimagined is showcasing the development of learner-centered ecosystems in communities across the United States.

All photos were taken by Sam Chaltain

Source link