Foreign Student Fees “Powerful Lever” for Autocratic Nations

Relying on international student tuition fees has provided authoritarian countries such as China with a “powerful lever” to use against U.S. universities, an academic has warned.

With the U.S. having long depended on overseas students, the Trump administration is making the issue worse, according to Sarah McLaughlin, a senior scholar on global expression at the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression.

“With all these funding cuts, it is going to force universities to have to look elsewhere for funding … and I don’t think it’s a grand mystery [that] they might consider looking to expand ties to improve funding,” she told Times Higher Education.

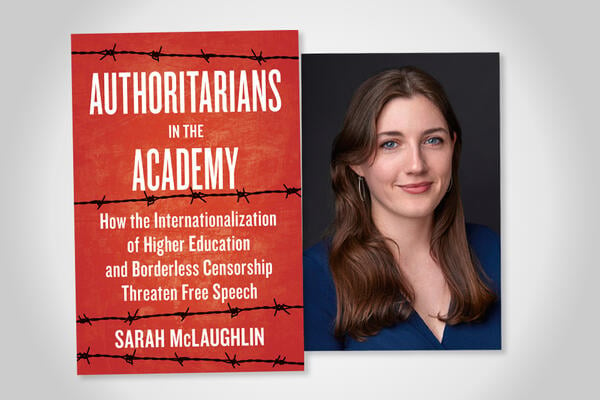

In her new book, Authoritarians in the Academy: How the Internationalization of Higher Education and Borderless Censorship Threatens Free Speech (Johns Hopkins University Press), McLaughlin examines how foreign authoritarian influence is undermining freedom and integrity within U.S. universities, including focusing on the “borderless censorship” of countries like China, which has been accused of pressuring students from afar.

McLaughlin said Beijing was increasingly relying on emotional arguments about universities’ responsibility to avoid offending China as a way of shutting down discussions around the sovereignty of Hong Kong or Taiwan.

The book warns that colleges are recruiting international students without worrying about their “basic expressive rights.”

“The unfortunate thing about international students here in the U.S. is that the more universities want and need them to fill up space in the university to provide much-needed tuition dollars, the greater incentive there is for them to ignore those students’ rights and concerns,” said McLaughlin.

“If you really need that funding source, you might not want to engage in any activity that’s going to threaten it.”

As a result, China and other well-populated authoritarian countries have a “powerful lever … to pull against noncompliant universities”—the power to deny universities millions of dollars in tuition payments.

“When you put together the presence of international students, the funding, the relationships, the ties on the whole, those countries have gained more than the U.S. has, but that’s only because universities have allowed this issue to go unchallenged,” said McLaughlin.

“I want international students to continue to be a major force in American higher education, but not without real understanding of the specific free speech issues and cultural concerns that come with those students.”

The book compares higher education to Hollywood—both industries that once thought they had the power to liberalize China, which have now become dependent on and changed by participation in the Chinese market.

“Outside of maybe providing VPN access, I don’t think American universities have brought any new kinds of freedoms within China, but I do think they have brought in really worrying incentives into their own operations to maintain those partnerships,” McLaughlin continued.

“At its core, I think they have prioritized the reputation of being a global institution and the money that comes with it more than anything else.”

While China is the “lead story” when it comes to censorship from abroad, McLaughlin said universities were also guilty of expanding into the Gulf states without understanding the pressures this will put on their values.

“It’s the same kind of thing that we’ve seen with FIFA, with the Olympics. It’s pretty basic stuff: Whenever you have a global industry that chooses to expand, it’s going to face these pressures, and it’s just a greater concern when the one doing that is higher education.”

McLaughlin warns that higher education’s “business as usual” expansion into such countries as the United Arab Emirates is the fastest way to normalize behavior like the abuse of British researcher Matthew Hedges, who was tortured in prison in the U.A.E. after being accused of spying for the U.K. government. (He was later pardoned.)

“[Gulf states] are trying to entice these global institutions that are highly respected to their country because of the patina of respectability that it gives,” McLaughlin said. “If universities think that what they’re doing there is worth perhaps giving that PR hit to those countries, then so be it.”

While there is no “silver bullet” to fix the problems, McLaughlin said all institutions should offer their international students explainers on what their rights are and anonymous reporting lines on transnational repression and ensure their overseas partnerships are not “rubber-stamping” rights violations.

And if U.S. higher education survives its own domestic problems, she said this creates an opportunity for universities to “reimagine” how they deal with authoritarian censorship abroad.

“I don’t want them to do the right thing and fight back against the Trump administration just to allow similar threats from foreign governments to go unchallenged,” she said. “I hope that this can be taken as an opportunity for universities to really reject authoritarianism from every source.”

Source link