Faculty Warn Against State Bans on H-1B Visas

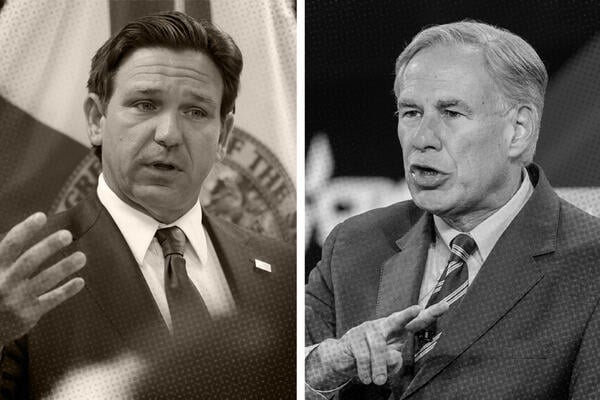

First, President Trump placed a $100,000 fee on new H-1B visa applications in September. Then a month later, Florida’s governor Ron DeSantis urged his university board to “pull the plug” on visa-holding employees. And now, this week, Texas governor Greg Abbott has ordered his own one-year visa freeze and Florida’s university board is set to consider a similar one today.

And while the H-1B program can only be used to hire foreign talent for specialty occupations that require highly specialized skill sets, data shows that collectively these actions could affect tens of thousands of new employees each year—many of whom work at colleges and universities.

U.S. colleges and universities hired more than 16,000 workers on approved H-1B visas in the first three quarters of 2025—making up about 5 percent of the overall total, an Inside Higher Ed data analysis showed. Nearly half of them were at just 50 institutions, six of which were located in Texas and Florida. Many of those roles across the sector were at research and medical centers.

For months, faculty unions, academic associations and advocates for international scholars have warned that Trump’s crackdown on the H-1B visa program could damage university research. But now they say these new and proposed state-level bans have become a threat to academic freedom and institutional autonomy.

“It’s also a restriction in academic freedom, because it’s telling departments, ‘Here’s a group of scholars who are off-limits to you, even if they’re doing research or if they’re able to teach in areas that you think are really important for your students,’” said Brendan Cantwell, a higher education professor at Michigan State University. “‘Even if you find someone who you think can make advances in this field and support the mission of your department in the university, you can’t hire them.’”

Cantwell previously warned that Trump’s proposed $100,000 fee on new visa applicants could be devastating, as colleges and universities depend on faculty members and staff with niche expertise. Without an international market, he said, many may struggle to fill vital roles, especially in science and engineering fields.

In seeking to restrict the use of the H-1B program, state and federal officials have argued that employers are abusing the program and using it as a way to avoid hiring American workers. This crackdown is part of the administration’s broader push against both illegal and legal immigration.

“Rather than serving its intended purpose of attracting the best and brightest individuals from around the world to our nation to fill truly specialized and unmet labor needs, the program has too often been used to fill jobs that otherwise could—and should—have been filled by Texans,” Abbott wrote Tuesday in a letter to agencies and public universities.

The Texas freeze will run through May 31, 2027, while the proposed Florida pause will end Jan. 5 of next year. Abbott is also seeking data on current H-1B visa–holding employees at public universities.

Texas AAUP-AFT, a faculty-led union that defends professors’ academic freedom, said in a statement that restrictions on international talent could significantly limit universities’ ability to compete on the global innovation stage—especially in fields like science, technology, engineering and medicine.

“Messing with the H-1B system was a bad idea when President Trump first tried it. It’s even more reckless when it’s a governor undermining his own state’s workforce,” Brian Evans, president of Texas AAUP-AFT, said in a news release Tuesday. “Nowhere will that impact be more pronounced than our world class university medical centers.”

About 40 percent of the visas issued to employees at public universities in 2025 went to workers at medical or health institutions, according to an AAUP analysis of federal data.

And while so far the bans enacted or proposed in Texas and Florida only apply to new visa applicants, much remains unclear about the ability of existing visa-holding employees to renew. Workers with an H-1B visa can stay and work for up to six years before they have to reapply.

Florida’s 12 public universities were approved for 637 visas in fiscal year 2025; the University of Florida had the most at 252. Meanwhile, in Texas, several public universities were among the 100 employers that had approved H-1B visa holders. The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center ranked 16th with 228 visas and was followed by Texas A&M University with 214. The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, the University of Texas at Austin and Texas Tech University all employed more than 100 approved visa holders.

Miriam Feldblum, co-founder of the Presidents’ Alliance on Higher Education and Immigration, said American universities’ ability to attract the best and most talented individuals both domestically and globally has made them the crown jewel of academia. And to bar new international scholars from coming to the States, as Texas has, would hurt not only them but all of the students, patients and colleagues they interact with on a daily basis.

“We sometimes focus on the loss of opportunity for the individual, but their loss is really going to be our loss,” she said. “We’re talking about a small number of H-1B visa holders among the whole group of faculty and professionals on campus. But we know that they make outsized contributions and are important to the functioning, teaching and operations of the institutions.”

To Cantwell, the fact that Abbott’s decision came just days before the scheduled vote in Florida appears to be yet another demonstration of governmental copycat, as both states show a growing desire to align with the Trump administration in terms of higher education policy, reform and restriction.

“There is ambiguity created by the chaos from the federal government, and these state governments are trying to provide some—I don’t mean this in a positive way—but they’re providing clarity to their colleges and universities,” he said. “[Governors] are saying, ‘Hey, even if you think the federal government allows this under some conditions, we’re telling you we don’t want you to do it.’”

Some, like Cantwell, believe the political dynamics in Texas and Florida are unique and that other Republican states won’t be as quick to implement a similar pause. But in recent years a number of Republican-led states have followed in Texas and Florida’s footsteps and passed legislation that overhauls higher ed policy for public institutions.

$100K Fee Still Looms

But even in states that don’t pause H-1B visa applications, universities could struggle to recruit foreign workers thanks to Trump’s $100,000 fee.

International workers who are already legal residents will not be required to pay the fee, even if they are up for renewal or are moving between employers. But with up to hundreds of new visa recipients hired at top research institutions each year, the hefty price tag will likely continue to be a significant burden.

Some, including the AAUP and the Association of American Universities, have challenged the fee in court, but judges have yet to block it. (A federal judge dismissed the AAU lawsuit late last year.)

Inside Higher Ed reached out to the top 10 universities with the most visa applications to ask what their plan was moving forward in response to the fee, but only one—the University of California, San Francisco—replied prior to publication.

“The University continues to monitor updates related to the H-1B visa fee increase and values the contributions and expertise of our international staff and faculty,” a university spokesperson said in an email.

Still, Feldblum is trying to remain optimistic. She said many of the universities she’s talked to are doing what they can to protect and continue employing academic experts from around the globe.

Trump’s guidance noted that colleges can seek case-by-case exemptions from the fee, but little detail was provided as to what standards will be used to determine which employees earn immunity and which do not. That, combined with the pending court cases, have left many university leaders in a holding pattern, she said.

So for now, Feldblum explained, “It’s not a one-pronged approach. Leaders are really looking to make sure they’re doing things in the best interest of their university’s mission and capacity.”

Source link