7 Teaching Practices that Nurture Student Voice

Listen to the interview with Shane Safir, Marlo Bagsik,

Crystal Watson, and Sawsan Jaber (transcript):

Sponsored by Listenwise and Solution Tree

In our efforts to improve school, especially in the United States, student voice has really gotten lost. We focus on test scores, top-down curriculum, and measures of success that never quite get to the humanity of our students. Not only have these efforts not succeeded in raising test scores (Schwartz, 2025), they haven’t given us much satisfaction in other ways, either: In a recent survey, nearly half of educators reported that student behavior was worse than before the pandemic, and that number had grown since teachers were surveyed just two years earlier (Stephens, 2025).

Although there are most certainly individual schools where great things are happening, too many schools are still missing the mark. Too many schools keep trying to address these problems without hearing from the very people who are impacted most: the students.

But there is another way. Four years ago, I started talking a lot about a new book I’d read called Street Data. The book offered an approach to school improvement that was different from anything I’d seen before. It focused on having slow, thoughtful listening sessions with students at the margins, those whose voices were rarely heard and whose needs weren’t being consistently met at school. From those sessions, new solutions could be developed, piloted, and then iterated and improved on, followed by more listening sessions to guide further change.

Unlike so many other programs and approaches I’d seen for making schools better — many of which are quite expensive to implement — the model outlined by this single book seemed like it could actually work. I really wanted teachers and school leaders to try it.

So I started by having the authors, Shane Safir and Jamila Dugan, on episode 178 of the podcast. Not long after, I offered to produce a mini-documentary of Shane and Jamila guiding two schools through the Street Data process, so that teachers could get an up-close look at how the approach worked. A year later, I published an eight-episode video series and had a few of the participants join me on the podcast to talk about the project; you can hear that conversation on episode 203.

As the Street Data methodology made its way into more schools, one question that came up often was What does it look like when teachers center student voice and student agency in their pedagogy? If a school is invested in the Street Data process and in shifting their practices, what kinds of practices might they actually use in the classroom?

To answer that question, Shane Safir teamed up with three educators: Marlo Bagsik, Sawsan Jaber, and Crystal Watson. Together, they wrote the new book Pedagogies of Voice: Street Data and the Path to Student Agency.

Rather than prescribing a single rigid approach, the book functions as a “seed store” of practices, a rich collection of small, replicable moves that educators can use to center student voice, nurture agency, and create space for meaningful learning.

This book is especially important now, in a time when marginalized voices, which had just begun to gain long-overdue recognition, are being aggressively pushed back into the margins. Across the country, books are being banned, teachers are being censored, and democracy is being threatened daily. For educators wondering where to put their energy in these frustrating and scary times, Pedagogies of Voice offers a powerful answer: Teach in a way that amplifies student voice. Create spaces where students can reflect, speak, and act, and where democratic practices like listening, challenging different opinions, and collaborating can thrive. Help them grow into the kind of people who will reshape the world for the better.

On the podcast, I talk with the book’s four authors. Each one shares one or two of their favorite classroom practices from the book — specific, actionable strategies you can try right away. You can listen to the interview in the player above, read the full transcript here, or check out the overview of the practices below.

The Four Domains: Identity, Belonging, Inquiry, and Efficacy

The book organizes classroom practices into an Agency framework made up of four domains: identity, belonging, inquiry, and efficacy. Our sampling of practices comes from each of these.

Practices that Awaken Identity

The practices in this domain help us create learning spaces in which every learner can say, “My ways of being, knowing, and learning are valued here.” The two strategies shared by Sawsan Jaber are both ways of practicing storientation, which uses stories as a springboard for learning and identity development.

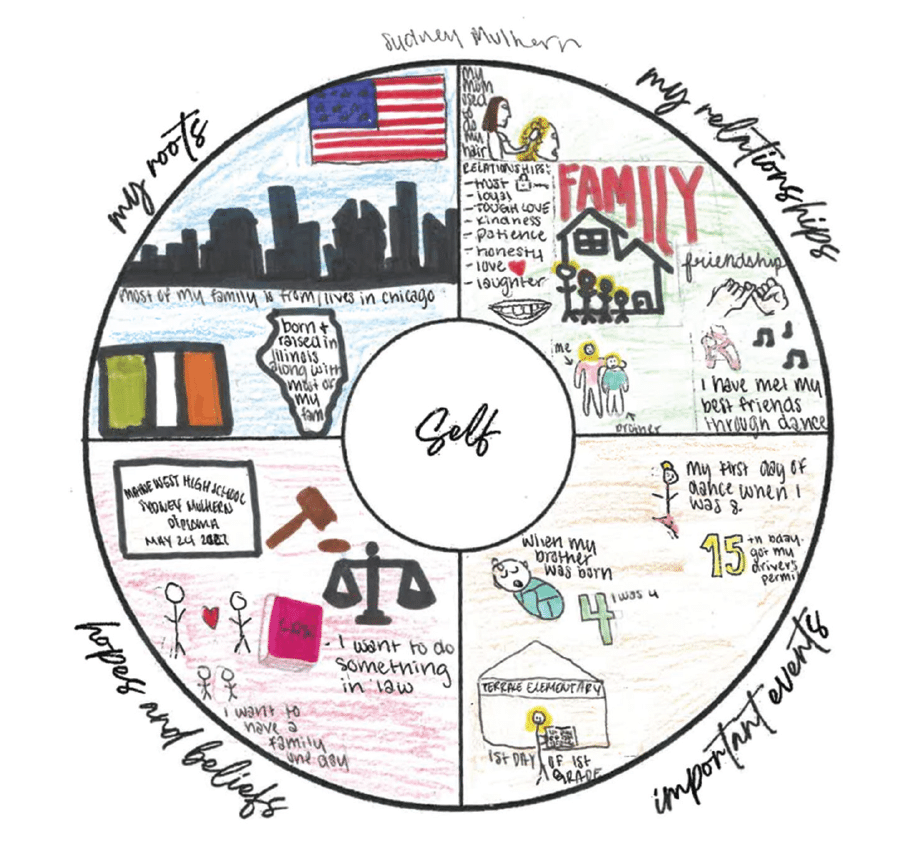

- Identity Mandalas

These circular representations of a student’s ancestry and unique life experiences offer students an opportunity to express their identity in a deep and thoughtful way. “For teachers that are looking for below the iceberg, get-to-know-you activities with students,” Jaber says, “this is definitely one that combines both art and words and deep interrogation.”

- Math Autobiographies

These projects ask students to explore and share their experiences of mathematics (both positive and challenging) in whatever format works for them — writing, art, video — as a way to humanize a subject that is often treated like it’s strictly made up of facts and figures. “I always struggled as a student with math,” Jaber says. “And I think that if this strategy was used by my math teachers, my experience would have looked very, very different.”

Practices that Awaken Belonging

This domain focuses on practices that make each student feel seen and loved in the classroom. For her share, Crystal Watson focused on a single practice, circling up, which is just what it sounds like: placing classroom seats in a circle for a variety of activities. Although it’s simple, it has a big impact on students’ sense of belonging.

“I just love the fact that when you circle up, you’re all equidistant from the center,” Watson explains. “At any given time, an identity, an idea, a person can be centered. We’re not centering one or or two identities or thoughts or ideals. We can center them all at any given time in our time together.”

Because much of her work focuses on math education, she has found circling up to be especially powerful in this subject area because it invites conversation. When she asks people who profess to hate math to explain why, they say, “You just sit there and do problems. That’s the problem. It should be more conversational. Argumentation should be a part of the math classroom.”

Practices that Awaken Inquiry

The practices in this domain empower students to ask questions and build knowledge in increasingly complex ways. “Inquiry has been stripped from the learning environments, so many places,” Safir says. “The ability for young people to wrestle with big questions about the world, to be curious, to stay curious, to develop not just literacy, but critical literacy about text, about media, about the world.”

- Wonder Wall

In this activity, students generate questions: “What are they genuinely wondering about the world or the communities they inhabit?” Safir explains. “And they don’t just say it on a post-it or to a partner; they create a visual wall of their questions.” From there, the questions can be drawn upon as prompts for discussions or journal entries. - The Sort

With this activity, students are given lots of little strips of paper that have an array of “answers” on them. “At an elementary school classroom,” Safir explains, “it might be like 10, 15, or 20. In high school, it might be 75 to 80. And then kids sort the responses to activate their critical inquiry around what they think. So for example, at an elementary school classroom, it might be, what is good for kids? And you give them examples like allowance, not having a uniform, doing chores, a stay-at-home parent, music lessons, and they’re debating, discussing, and sorting. At the high school level, a more sophisticated one, who are the 10 most and 10 least important figures in US history? Through that pedagogy, students are driving the learning, they’re carrying the cognitive load, they’re thinking about what’s important, and they’re having to learn to articulate and defend their responses.”

Practices that Awaken Efficacy

In this domain, the focus is on creating learning spaces in which every learner believes they can make a difference around issues that matter to them. Marlo Bagsik shared two practices in this domain that work together to bookend a week:

- Intention Mondays

Bagsik likes to begin each week by having students set intentions for the week with a 5-7-minute prompt like this: “In three sentences, think about the week ahead of us — in classes, at home, at school, and any other spaces that matter to you. What actions, tasks, and/or things do you want to see happen that you have control over?” This activity not only gives students an opportunity to consider their areas of influence, but it also provides Bagsik with important information about what’s going on in students’ lives. - Reflection Fridays

At the end of the week, students are asked to reflect on what they’ve learned from their experiences in class the previous week, using a prompt like: “In three sentences, reflect on the DO NOWs, assignments, readings, notes, discussions, and conversations we have had in class this past week. What moments do you remember and why? Share one significant moment that stayed with you and what it meant to you.”

Join our mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration that will make your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to our members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Over 50,000 teachers have already joined—come on in.