They can’t count on federal money

ASHE COUNTY, N.C. — In the time it took to read an email, the federal money vanished before Superintendent Eisa Cox’s eyes: dollars that supported the Ashe County school district’s after-school program, training for its teachers, salaries for some jobs.

The email from the Department of Education arrived June 30, one day before the money — $1.1 million in total — was set to materialize for the rural western North Carolina district. Instead, the dollars had been frozen pending a review to make sure the money was spent “in accordance with the President’s priorities,” the email said.

In a community still recovering from Hurricane Helene, where more than half of students are considered economically disadvantaged, Cox said there was no way they could replace that federal funding. “It is scary to think about it, you’re getting ready to open school and not have a significant pot of funds,” she said.

School leaders across the country were reeling from the same news. The $1.1 million was one small piece of a nearly $7 billion pot of federal funding for thousands of school districts that the Trump administration froze — money approved by Congress and that schools were scheduled to receive on July 1. For weeks, leaders in Ashe County and around the country scrambled to figure out how they could avoid layoffs and fill financial holes — until the money was freed July 25, after an outcry from legislators and a lawsuit joined by two dozen states.

“I had teachers crying, staff members crying. They thought they were going to lose their jobs a week before school,” said Curtis Finch, superintendent of Deer Valley Unified School District in Phoenix.

Now, as educators welcome students back to classrooms, they can no longer count on federal dollars as they once did. They must learn to plan without a playbook under a president intent on cutting education spending. For many districts, federal money is a small but crucial sliver of their budgets, potentially touching every part of a school’s operations, from teacher salaries to textbooks. Nationally, it accounts for about 14 percent of public school funding; in Ashe County, it’s 17 percent. School administrators are examining their resources now and budgeting for losses to funding that was frozen this summer, for English learners, after-school and other programs.

So far, the Trump administration has not proposed cutting the largest pots of federal money for schools, which go to services for students with disabilities and to schools with large numbers of low-income students. But the current budget proposal from the U.S. House of Representatives would do just that.

At the same time, forthcoming cuts to other federal support for low-income families under the Republican “one big, beautiful bill” — including Medicaid and SNAP — will also hammer schools that have many students living in poverty. And some school districts are also grappling with the elimination of Department of Education grants announced earlier this year, such as those designed to address teacher shortages and disability services. In politically conservative communities like this one, there’s an added tension for schools that rely on federal money to operate: how to sound the alarm while staying out of partisan politics.

For Ashe County, the federal spending freeze collided with the district’s attempt at a fresh start after the devastation of Helene, which demolished roads and homes, damaged school buildings and knocked power and cell service out for weeks. Between the storm and snow days, students here missed 47 days of instruction.

Cox worries this school year might bring more missed days: That first week of school, she found herself counting the number of foggy mornings. An old Appalachian wives’ tale says to put a bean in a jar for every morning of fog in August. The number of beans at the end of the month is how many snow days will come in winter.

“We’ve had 21 so far,” Cox said with a nervous laugh on Aug. 21.

Related: A lot goes on in classrooms from kindergarten to high school. Keep up with our free weekly newsletter on K-12 education.

Fragrant evergreen trees blanket Ashe County’s hills, a region that bills itself as America’s Christmas Tree Capital because of the millions of Fraser firs grown for sale at the holidays. Yet this picturesque area still shows scars of Hurricane Helene’s destruction: fallen trees, damaged homes and rocky new paths cut through the mountainsides by mudslides. Nearly a year after the storm, the lone grocery store in one of its small towns is still being rebuilt. A sinkhole that formed during the flooding remains, splitting open the ground behind an elementary school.

As students walked into classrooms for the first time since spring, Julie Taylor — the district’s director of federal programs — was reworking district budget spreadsheets. When federal funds were frozen, and then unfrozen, her plans and calculations from months prior became meaningless.

Federal and state funding stretches far in this district of 2,700 students and six schools, where administrators do a lot with a little. Even before this summer, they worked hard to supplement that funding in any way possible — applying to state and federal grants, like one last year that provided money for a few mobile hot spots for families who don’t have internet access. Such opportunities are also narrowing: The Federal Communications Commission, for example, recently proposed ending its mobile hot spot grant program for school buses and libraries.

“We’re very fiscally responsible because we have to be — we’re small and rural, we don’t have a large tax base,” Taylor said.

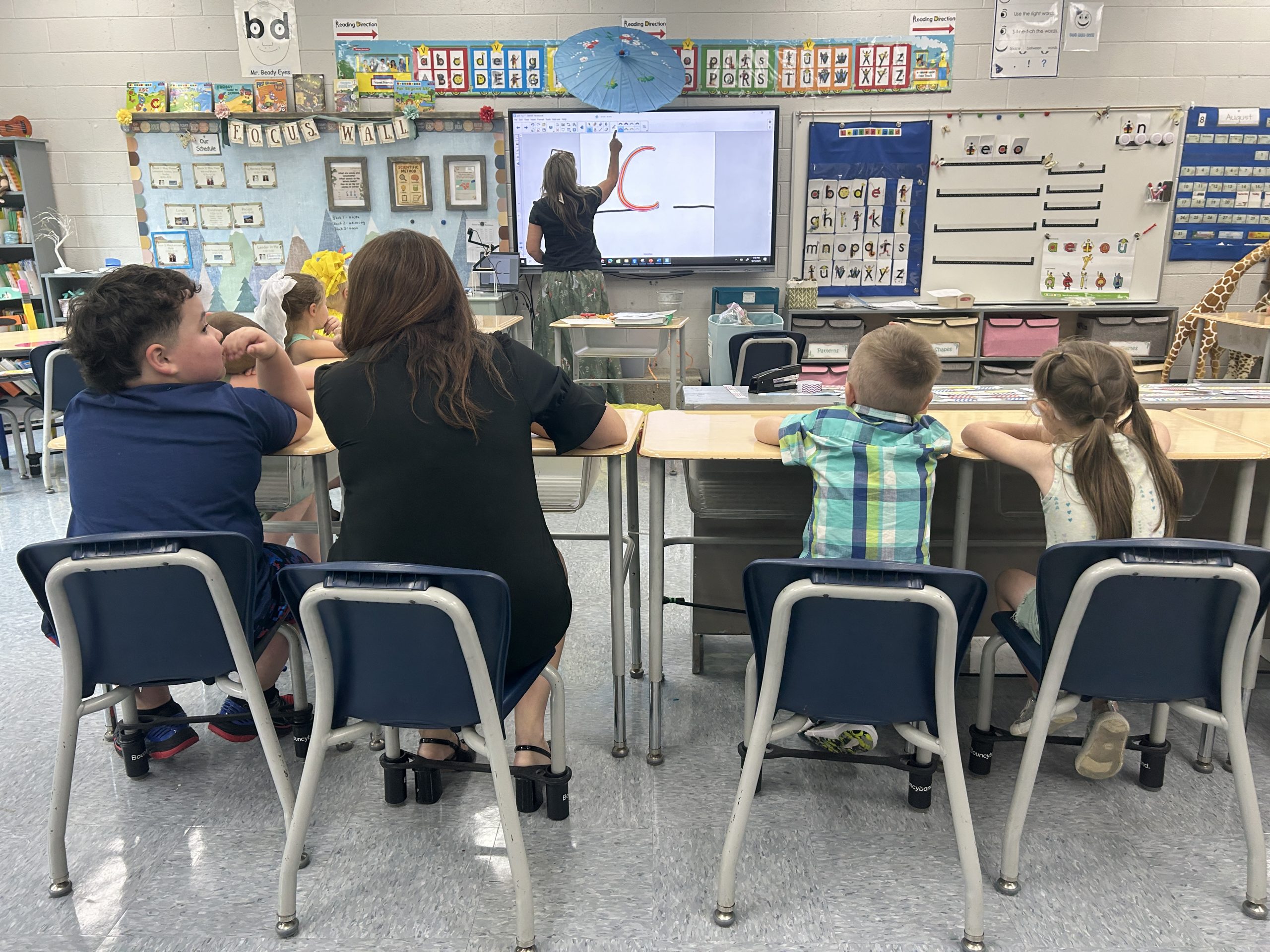

When the money was frozen this summer, administrators’ minds went to the educators and kids who would be most affected. Some of it paid for a program through Appalachian State University that connects the district’s three dozen early-career teachers with a mentor, helps them learn how to schedule their school days and manage classroom behavior.

The program is part of the reason the district’s retention rate for early career teachers is 92 percent, Taylor said, noting the teachers have said how much the mentoring meant to them.

Also frozen: free after-school care the district provides for about 250 children throughout the school year — the only after-school option in the community. Without the money, Cox said, schools would have to cancel their after-school care or start charging families, a significant burden in a county with a median household income of about $50,000.

The salary for Michelle Pelayo, the district’s migrant education program coordinator for nearly two decades, was also tied up in that pot of funding. Because agriculture is the county’s biggest industry, Pelayo’s work in Ashe County extends far beyond the students at the school. Each year, she works with the families of dozens of migrant students who move to the area for seasonal work on farms, which generally involves tagging and bundling Christmas trees and harvesting pumpkins. Pelayo helps the families enroll their students, connects them with supplies for school and home, and serves as a Spanish translator for parent-teacher meetings — ”whatever they need,” she said.

Kitty Honeycutt, executive director of the Ashe County Chamber of Commerce, doesn’t know how the county’s agriculture industry would survive without the migrant students Pelayo works with. “The need for guest workers is crucial for the agriculture industry — we have to have them,” she said.

A couple of years ago, Pelayo had the idea to drive to Boone, North Carolina, where Appalachian State University’s campus sits, to gather unwanted appliances and supplies from students moving out of their dorm rooms at the end of the year to donate to migrant families. She’s a “find a way or make a way” type of person, Honeycutt said.

Cox is searching for how to keep Pelayo on if Ashe County loses these federal funds next year. She’s talked with county officials to see if they could pay Pelayo’s salary, and begun calculating how much the district would need to charge families to keep the after-school program running. Ideally, she’d know ahead of time and not the night before the district is set to receive the money.

Related: Trump’s cuts to teacher training leave rural districts, aspiring educators in the lurch

Districts across the country are grappling with similar questions. In Detroit, school leaders are preparing, at a minimum, to lose Title III money to teach English learners. More than 7,200 Detroit students received services funded by Title III in 2023.

In Wyoming, the small, rural Sheridan County School District 3 is trying to budget without Title II, IV and V money — funding for improving teacher quality, updating technology and resources for rural and low-income schools, among other uses, Superintendent Chase Christensen said.

Schools are trying to budget for cuts to other federal programs, too — such as Medicaid and food stamps. In Harrison School District 2, an urban district in Colorado Springs, Colorado, schools rely on Medicaid to provide students with counseling, nursing and other services.

The district projects that it could lose half the $15 million it receives in Medicaid next school year.

“It’s very, very stressful,” said Wendy Birhanzel, superintendent of Harrison School District 2. “For a while, it was every day, you were hearing something different. And you couldn’t even keep up with, ‘What’s the latest information today?’ That’s another thing we told our staff: If you can, just don’t watch the news about education right now.”

Related: Tracking Trump: His actions on education

There’s another calculation for school leaders to make in conservative counties like Ashe, where 72 percent of the vote last year went for President Donald Trump: objecting to the cuts without angering voters. When North Carolina’s attorney general, a Democrat, joined the lawsuit against the administration over the frozen funds this summer, some school administrators told state officials they couldn’t publicly sign on, fearing local backlash, said Jack Hoke, executive director of the North Carolina School Superintendents’ Association.

Cox sees the effort to slash federal funds as a chance to show her community how Ashe County Schools uses this money. She believes people are misguided in thinking their schools don’t need it, not malicious.

“I know who our congresspeople are — I know they care about this area,” Cox said, even if they do not fully grasp how the money is used. “It’s an opportunity for me to educate them.”

If the Education Department is shuttered — which Trump said he plans to do in order to give more authority over education to states — she wants to be included in state-level discussions for how federal money flows to schools through North Carolina. And, importantly, she wants to know ahead of time what her schools might lose.

As Cox made her rounds to each of the schools that first week back, she glanced down at her phone and looked up with a smile. “We have hot water,” she said while walking in the hall of Blue Ridge Elementary School. It had lost hot water a few weeks earlier, but to Cox, this crisis was minor — one of many first-of-the-year hiccups she has come to expect.

Still, it’s one worry she can put out of her mind as she looks ahead to a year of uncertainties.

Meanwhile, the anxiety about this school year hasn’t reached the students, who were talking among themselves in the high school’s media center, creating collages in the elementary school’s art class and trekking up to Mount Jefferson — a state park that sits directly behind the district’s two high schools — for an annual trip.

They were just excited to be back.

Marina Villeneuve contributed data analysis to this story.

Contact staff writer Ariel Gilreath on Signal at arielgilreath.46 or at gilreath@hechingerreport.org.

This story about public school funding was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter.

Source link