A Year of Grace | Getting Smart

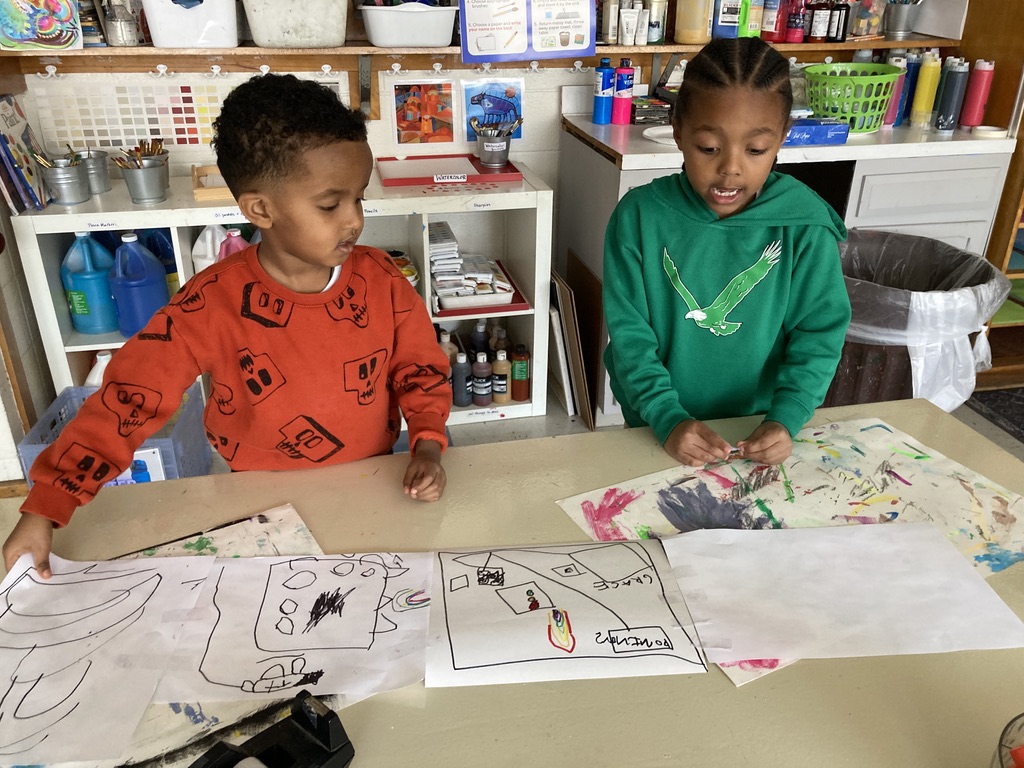

All photos by Sam Chaltain

In these final weeks of August, as summer’s meandering pace winds down, a new school year across the country is gradually getting underway.

How should those 180 days best be spent? And of all the things our schools could place at the center of their curricula, what choices would allow kids not just to learn something new, but create something beautiful and lasting in the process?

Last year, I had the honor of watching one community answer that question over the course of the entire year — in the most child-affirming, magical way.

Grace Episcopal is not the first place you’ll name when you think of schools in the nation’s capital.

No president’s kids have ever gone here.

There’s no waiting list to navigate, or multimillion dollar renovation to wait out.

Technically, it’s not even in DC.

And yet, for the kids and families that have found their way there, Grace is a developmental oasis, nestled within a 1950s-era school building and a protective circle of century-old trees that line the limits of its eleven-acre footprint in an easy-to-miss corner of southern Maryland.

Since 2016, it has been led by Jennifer Danish, a loving, longtime local educator who has steadily shaped Grace into becoming, in her words, “a joyful and inclusive learning environment rooted in wonder, purpose and belonging.”

On a mild morning in early September 2024 — the first day of the new school year — that culture was on display as Danish and Poncho, the placid puppy she was training to become a guide dog, stood near the school’s front doors to welcome 102 children back to school.

For most, it was a homecoming to a trusted, familiar place. The older students hugged their teachers, chatted wildly with one another, and besieged Poncho with a blur of probing pets. “We lose some families because we don’t have a middle or high school,” Danish explained as a sea of small bodies shimmered around her, “but the lack of adolescents allows us to create an environment that is fully about the joy and wonder of childhood.”

Indeed, Grace enrolls students as young as two, so for the littlest arrivals, this was not merely the first day of the year, but their first-ever day at school — something for which Priya Ghosh and Einat Moskof were prepared.

Like the rest of Grace’s faculty, Ghosh and Moskof are veteran practitioners — the sorts of “warm demanders” Danish always looked for in her new hires. But Ghosh and Moskof also possessed a more specific type of expertise, one that was central to Jen Danish’s ultimate vision for the school: they were skilled practitioners in the philosophy of Reggio Emilia.

Although it is not widely known outside of educator circles, Reggio Emilia is an Italian city that, in the wake of the second World War’s conclusion, gave birth to a progressive pedagogy that has since yielded the finest nursery schools in the world — and an integrated public system of more than eighty early childhood centers that claim more than 14% of the city budget — a stunning civic commitment that has spanned almost a century’s worth of political slings and arrows.

“The Reggio system is a collection of schools for young children in which each child’s intellectual, emotional, social and moral potentials are carefully cultivated and guided,” commented the renowned developmental psychologist Howard Gardner.

And according to Loris Malaguzzi, one of Reggio’s founders, its core principles are a direct response to the era that preceded it. “Mussolini and the fascists made us understand that obedient human beings are dangerous human beings,” he explained. “When we decided to build a new society after the war, we understood that we needed to have schools in which children dared to think for themselves, and where children got the conditions for becoming active and critical citizens.”

What that means in practice is that the schools of Reggio Emilia — and the informal network of learning communities around the world that, like Grace, describe themselves as “Reggio-inspired” — enshrine a deep reverence for the dignity of childhood; offer immersive exposure to creative expression and materials; and enlist their students in the co-creation of meaningful long-term projects — all of which emerge anew each year, based on the particular interests of the group.

“Instead of an early push to read, for example,” explains Lella Gandini, Reggio’s U.S. liaison, “Reggio’s teachers support a competent ability to communicate with others through speech and other means, so that one can make a contribution to the group. And instead of long hours of practice at a skill, the emphasis is placed on establishing a meaningful and emotional reason to the subject matter — the content of the project.”

For Priya Ghosh and Einat Moskof, that meant each new school year was a chance first and foremost to uncover the thoughts and feelings of each new constellation of children — and, slowly, to identify a yearlong project that felt both right-sized for the group, and capable of letting them create something lasting together.

“We proceed in such a way that the children are not shaped by experience but are the ones who give shape to it,” said Moskof, as twelve four- and five-year-olds cautiously inspected their classroom, her, and one another.

“We want this to be a special place for all of you,” Ghosh told the group later, after they had gathered in a circle for the first time. “And so this year, we’re going to go on a journey.

“We don’t know what the story of that journey is yet,” she added. “But we’re going to figure it out, together.”

As the PreK classroom entered its second month of the school year, its teachers had begun to understand some essential features of the children in their care.

- Gabriel was flexible and creative.

- Charlie began each day eager for reconnection.

- Mila loved imaginative play.

- Otis could focus for extended periods of time.

- Asher narrated elaborate stories.

- Elijah was highly artistic.

- Brendan added depth and dimension to every classroom conversation.

- Zak was highly attuned to any changes in the environment.

- Imran could use drawing as its own form of language.

- Luna asked complex questions.

- Henrik was fascinated with maps.

- And Nandini loved to engage in dramatic play.

To complement the children’s different predilections, Ghosh and Moskof had to now identify a project that could envelop them all in a yearlong exploration.

For that task, Grace’s two PreK teachers added a third person to their team: the school’s atelierista, Jessica Boritz.

Priya, Einat and Jessica

In Reggio schools, each classroom is designed as its own atelier — which means that all of its learning spaces resemble a professional studio, with myriad artistic materials, and, ideally, ample room to create and explore. To maximize that commitment, Reggio schools employ an atelierista who floats between all the classrooms of the school and, as Anna Golden has explained, “scaffolds both children and teachers in messing about with, and developing relationships with media and materials. Together, the teachers and atelierista make sure there is enough time in the school schedule so that children can develop languages beyond written and spoken language in line with the school’s mission.”

So much of the work we ask children to complete in schools is so forgettable — a random piece of paper, crumpled up at the bottom of a backpack. At Grace, however, student work was always intentionally designed to be meaning-full. “Childhood is not simply a period of training to be an adult,” Boritz told me. “It is a distinct way of inhabiting the world, with important perspectives all its own. And so when we do it right, it can transform us, and change our position in the river of our own well-being.”

As the three women thought about the PreK classroom, they kept coming back to two beloved children’s books: Loren Long’s The Yellow Bus, which chronicles the full life cycle of a rusted old school bus; and Aleksandra and Daniel Mizielinski’s Welcome to Mamoko, which contains a myriad of overlapping stories depending upon which character you choose to follow.

“The bus is a big thing for these children,” Moskof said in an early planning meeting. “There is one that arrives here every day. But it’s also a little unknown — where does it come from? Where does it go when it leaves? That could be the sort of thing that really captures their imaginations and turns them into deeper investigators of their own surroundings.”

“And Welcome to Mamoko makes us think about how I may have my own story,” Ghosh added, “but I always need to consider how my story fits into the larger group.”

“It’s about bringing in different perspectives in multiple ways,” said Moskof. “But maybe let’s start by not showing them the pictures; only the audio. That way we can ask them how they would draw this story — the story of Grace!”

The next day, Grace’s PreK class listens to an audio version of The Yellow Bus. They are instantly mesmerized, and several propose drawing pictures to go with the story without prompting.

Then Asher makes an observation that will shape the next several months.

“The way this bus moves around makes me think of a map,” he says — an observation Henrik excitedly agrees with.

“That’s a good observation, Asher,” Moskof affirms. “What if we created a map to show the bus’s journey? The map could tell the story of the bus, and all the people and animals who come into contact with it.”

“Yes!” The group screams in unison.

By late January, Grace’s PreK classroom has been transformed into a map-making laboratory. Each child has drawn their own map, and they have begun to make a single shared one that is big enough for all of them to sit around.

Shortly after the idea of maps was first presented, the children transcended the story of the yellow bus, and became obsessed with “finding” their own houses, then the school, and finally, other important real or imaginary places that make up their own known worlds.

For Boritz, this created an opportunity to let the children express their identities through the design of their own houses in physical form. Using wood, paint, and loose parts, they spent the fall building their houses with a mixture of accurate and imagined attributes.

“What do you see when you look in there?” Moskof asks Elijah one morning as he peers into a window of his newly-constructed house.

“I see my eye looking big and scary. But this blue circle can open everything,” he says, pointing to a shiny addendum on the house’s outer wall. “It’s a button.”

“That’s the reflecting area of my house,” Luna adds, working nearby.

“What’s reflecting there?” her teacher asks.

“Me.”

“Maps are like written languages,” Ghosh tells me later, as the children enjoy their mid-morning snack. “They’re symbolic systems that encode information. So the children are both interpreting and creating their own map codes. But in the process, they’re also getting to construct all kinds of knowledge — from how to draw a house, to how to create a standing figure, label places, or make parts of the map moveable.”

“Seeing the kids’ different personal aesthetics come through really helps us understand them and their needs and preferences,” Boritz adds. “We’re using their work here to better understand them — and to help them better understand each other.

“The big question now is how we can use the map to record and elicit stories — and invite them into an even deeper process of co-creation.”

By the start of the second semester, the children’s map of their town has shifted from two to three dimensions, and each child’s physical house has found its proper place. Sometimes, that means it was accurately situated; but just as often, the children’s houses have been placed where they wish they could be, in close proximity to their closest friends.

Beyond its sudden verticality, however, the city they have created has become a mini-masterpiece.

A glimmering sun, complete with dangling strips of fabric as its rays, now hangs overhead.

At Luna’s insistence, a blood moon was also added, based on a festival celebration she once undertook with her family.

And an overhead projector has helped create an undulating blue ocean — one that has allowed Charlie to center his love of sea creatures.

It is a strikingly beautiful creation — and for Jessica Boritz, that is precisely the point.

“Toni Morrison once said that beauty was an absolute necessity,” she explained. “It’s not a privilege or an indulgence. We can’t do without it any more than we can do without dreams or oxygen. And I have conversations with children all the time to show me the truth of that.

“Recently, a little girl told me, ‘I know how to make art.’

“Can you tell me how you make art?” I asked her.

“Put a lot of colors, like a rainbow,” she said.

“How do you feel when you look at all of the colors?” I asked.

“I feel hearts,” she said! “I feel hearts just by looking at it. That’s what makes it art.”

For Boritz, that is what Reggio’s long-term projects make possible. “It’s the aesthetic dimension,” she continued — “what Reggio atelierista Vea Vecchi calls an aspiration to quality that makes us choose one thing over another. The beauty the children create serves as an example of what is possible for our school, or any school.

“Children have a right to beauty, not only to behold it, but to create and offer it.”

Throughout that beautiful space, as the children tinker, play, or narrate their own stories, their three teachers treat each conversation as an opportunity to help them think more expansively about whatever they’re confronting, and manage the tension and potential between the real and the imagined.

One morning, Moskof revisits the multi-story format of Welcome to Mamoko to help them make sense of their nascent shared city. “Why are there different stories in the same book?” she begins. “How does that relate to what we’re doing here? Are there many stories? Or only one?”

“Everyone makes their own story,” Elijah offers.

“Everyone doesn’t have the same story,” Gabriel adds. “They have their own questions and stories to tell.”

By the final month of the year, a small yellow bus that one of the children brought in has become the talisman for storytelling. When a child has a story to share, they hold the bus and move it around the town while they narrate.

Each morning, Einat and Priya listen patiently as different children spin tales of pizza deliverymen and playdates. “Our job here is simply to bear witness as imagination unfolds,” Jessica explains. “A child’s development is never linear; it’s a spiral.”

Priya holds Nandini’s hand as she holds the bus, facing the map, determining where it should head. Like the others, she is flowing throughout this constructed city like a giant sea bird — effortlessly, with wings spread wide.

Soon, the sun will set over the children’s imagined town. Until then, it is a total reflection of their world: the things that exist, alongside the things they dream of.

And there is room for everyone.

Source link