3 Fresh Strategies That Get Students Engaged With Texts

Listen to the interview with Brian Sztabnik and Susan Barber (transcript):

Sponsored by Listenwise and Solution Tree

This page contains Bookshop.org links. When you make a purchase through these links, Cult of Pedagogy gets a small percentage of the sale at no extra cost to you. What’s the difference between Amazon and Bookshop.org?

So much of the work we do in school involves reading and interacting with texts: books, stories, articles, poems, and textbooks make up a huge part of how we get information into students’ heads. This is especially true in English language arts classes, where literature has always been a staple of course content. And sometimes, in some classes, with some students … it can get pretty boring. Pretty dry. Your students might not be too terribly excited about the work they are required to do with texts.

That’s a problem Brian Sztabnik and Susan Barber want to solve. Both are high school English teachers who have spent the last decade working online to build community with other English language arts teachers through social media chats and on their blog, Much Ado About Teaching. Through that work, they’ve learned that many ELA teachers struggle to plan lessons that really engage their students.

So they began curating strategies to meet that need. Earlier this year, they put those lessons into a book, 100% Engagement: 33 Lessons to Promote Participation, Beat Boredom, and Deepen Learning in the ELA Classroom.

On the podcast, they shared three of the lesson ideas from the book. Each one is fun, low-tech, and gets students out of their seats and engaging actively with course material. If you and your students work with texts, I bet you’re going to want to try at least one of them in your classroom. The strategies are summarized below. You can listen to our conversation in the player above or read a full transcript here.

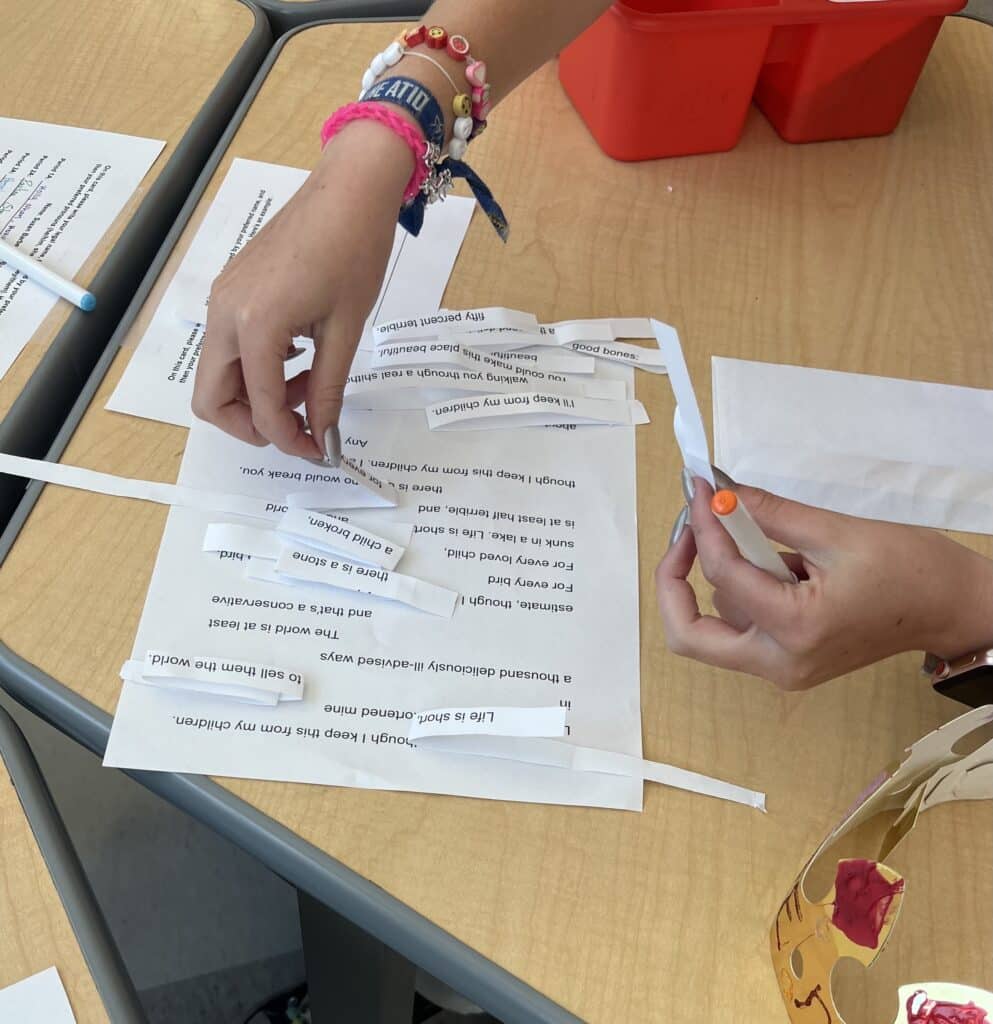

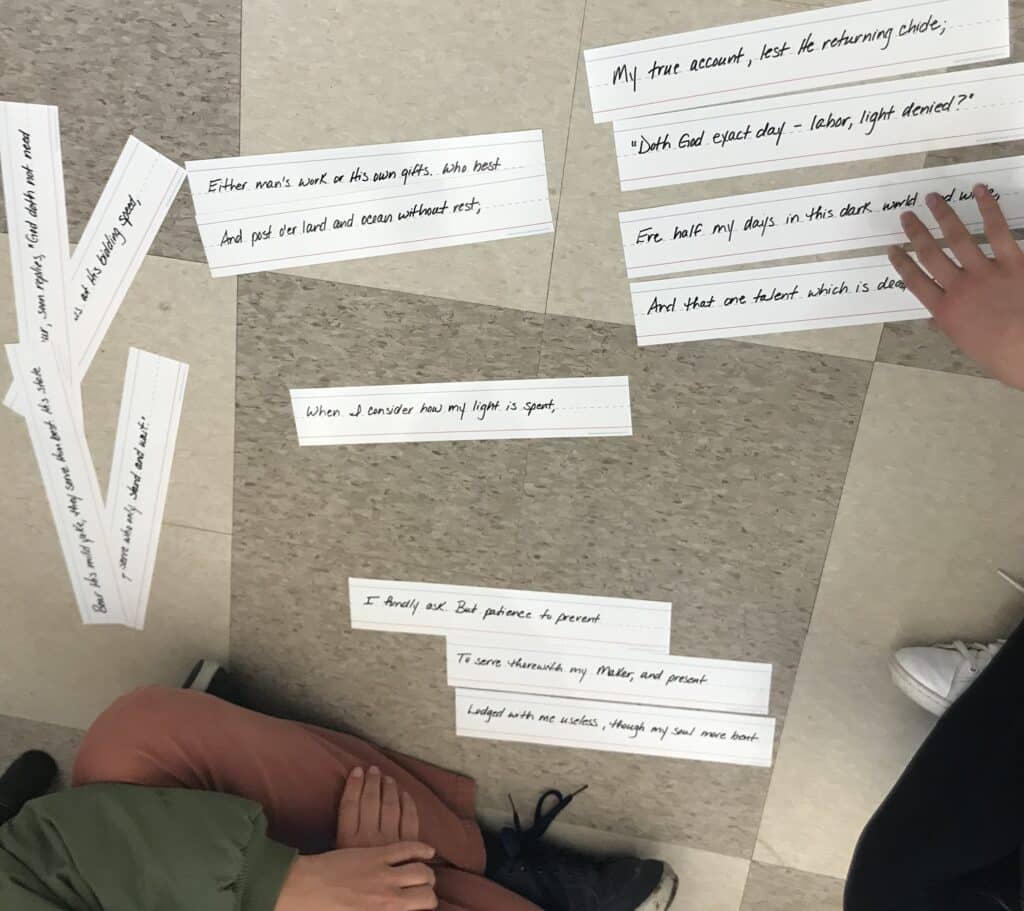

Strategy 1: Cutting Up Poems

In this lesson, students reconstruct a poem that has been cut into paper strips of individual words, phrases or lines, then annotate their version and compare it to the original.

“It’s forcing the students to do a close reading of the poem,” Barber explains. “If I would have passed out this poem and said, I want you to do a close reading, their eyes would be glazed over.”

But with this strategy, “They’re having to consider, Does this make sense if it goes here? Well, this is a capital letter, so it may not go in the middle of those sentences, or this is a comma here, that may not fit right there. And so students are already thinking about this poem analytically, and having really good discussion. They’re reading closely.”

“It’s a teacher trick,” she adds with a smile.

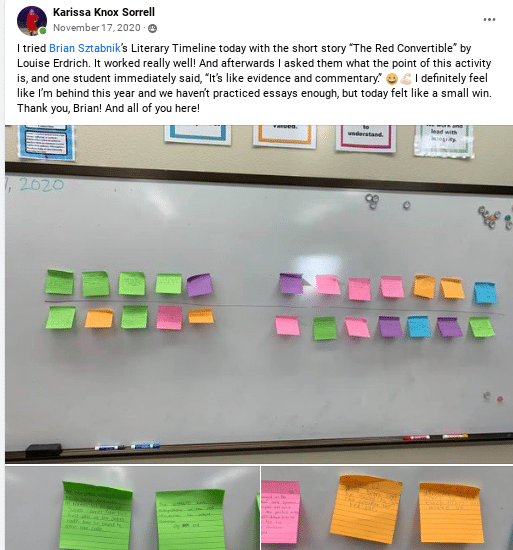

Strategy 2: Inferential Timeline

This lesson has students create a two-tiered timeline for a section in a novel. Each student is assigned a few pages of the section and an index card or post-it to place along the timeline. On their card, the student writes the most important thing to happen on those pages along with a quote that illustrates it. That card goes on top.

“What I’m really asking is to summarize the plot and boil it down to one or two sentences,” Sztabnik explains. “So this is all about decision-making and cutting out the extraneous details and just focusing on what’s really important. And often it’s either character development or increasing conflict or maybe a symbol finally emerges.”

Once the top row of cards is done, students then pick another student’s card from the wall and add a new card under it, explaining why that moment is significant.

“It’s collaborative without being collaborative physically,” Sztabnik says. “It’s collaborative mentally: They have to look at their classmate’s card, determine what happened, and make an inference about why that event was so important in the grand scheme of those chapters. So here’s where we’re getting to the higher level thinking — we can understand the plot; now we need to draw conclusions.”

The lesson ends with students doing a gallery walk of the whole timeline, taking notes about the inferences made by their classmates.

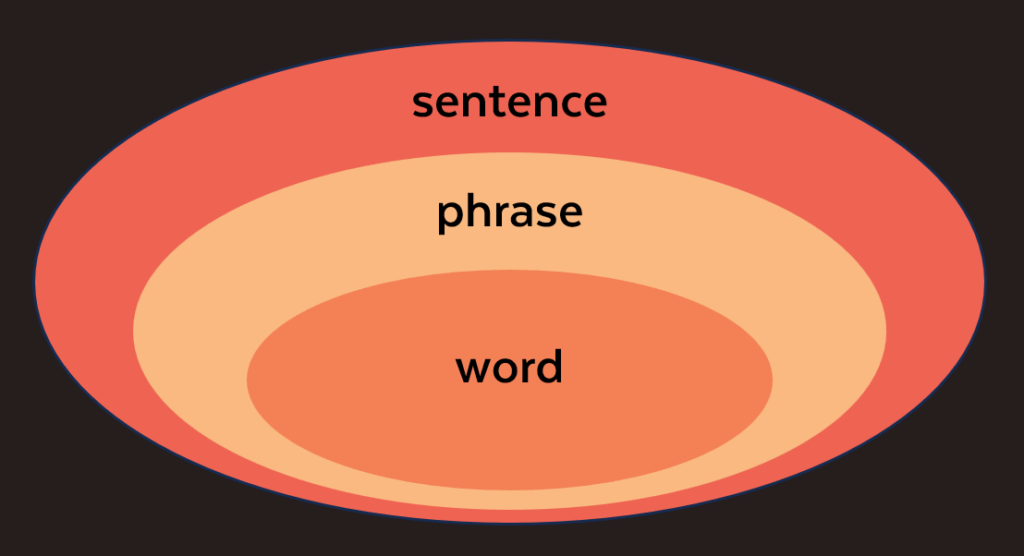

Strategy 3: Text Rendering

In this lesson, students start with a passage of text, then choose the most important sentence or line, the most important phrase or clause within that sentence, and finally the most important single word from that phrase.

After defending their choices to the rest of the class, small groups work together to draw conclusions about the passage.

Barber started doing this lesson to meet an academic need. “I have trouble every year getting students to narrow their focus when they’re making meaning from the text,” she explains. “They talk in these really big, general ideas, and I would be like, Where did this come from? And they’re like, You know, it’s just there. It has to come from someplace specific in the text. I had to find some activity to get them to take the big ideas to the small.”

Collaborate with Other Teachers on These Strategies

Sztabnik and Barber have created a Facebook group called 100% Engagement where teachers who are interested in these practices can learn from each other. And check out their blog, Much Ado About Teaching.

Join our mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration that will make your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to our members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Over 50,000 teachers have already joined—come on in.