How Can We Build Strategic Learning Organizations? The Power of ‘When’

CBE, PBL, PBE, PBIS, MTSS, UDL, STEM, AVID… the education landscape is an alphabet soup of programs, each promising to better serve all learners. The problem isn’t the programs themselves; it’s that they are often developed in a vacuum and claim to be a silver bullet, creating an exhausting cycle of disconnected initiatives that lack true alignment. Before you add the next program to the list, let’s consider how we can build strategic systems, rather than just a strategic plan.

Strategy isn’t just the “Why” (the vision) and “What” (outcomes). As a critical part of the Getting Smart Learning Innovation Framework, we ask “When?” to help strategically think about how to implement the Why, What, How, When, and Where of the framework.

A strategy requires thinking about this dynamic “When,” while traditional Strategic Planning can often turn it into a cautious, limiting exercise—the “how-we-fit-it-in.” This conventional planning can scale the bold vision down to meet conservative, current capacities, rather than allowing the vision to fully dictate the necessary “when” and “how” of resources and systemic change. These template-based planning processes can severely limit strategy, often by forcing known deliverables into a common, inflexible timeline. That’s where Strategic Direction comes in. This commitment to learning and iteration establishes clarity while remaining flexible, allowing for continuous reflection, feedback and data-informed adjustments as the work evolves.

How do schools and systems move past the fragmented initiatives and become strategic learning organizations?

Defining a Strategic System

Strategic systems consist of three integrated approaches:

- Directional. A Strategic Direction guided by clear priorities articulated by specific goals and accomplished via projects with appropriate Finance models to support the change initiative.

- Operational. A focused Research and Development program addresses adaptive challenges, while established Implementation protocols support technical challenges – with clear Success Metrics for both approaches.

- Relational. A thoughtful and adaptive approach to Leading Change through trust, clarity, and focus.

What is a Strategic Direction?

Understanding community needs, Community Vision (Why), is the foundation of any strategic direction. The process often begins with a reflection on past accomplishments, then proceeds to a review of the vision/mission, followed by the articulation of the strategy. Strategic directions offer flexibility to react to current and emerging conditions rather than being stuck in a rigid 3-5 year plan.

We believe that a strategic direction should be simple, clear, flexible, with measurable outcomes, and constant reflection and revision. While the nomenclature might vary, we always include the following structures:

- Priorities. Priorities are the larger elements/themes of the strategy and help organize strategic planning committee ideas into a coherent set of priorities. Priorities include a description and the “why” behind each priority, based on stakeholder feedback and system data.

- Goals. Goals articulate the specific targets that will be achieved for each priority.

- Success Metrics. Success metrics are specific to each goal and can be tracked by project completion or specific metrics attached to the goal.

- Projects. Each goal is broken down into a tangible set of possible projects, pilots, or initiatives. These projects can be significantly adjusted and modified throughout the strategic direction time frame.

Finances are often the limiting factor when setting a strategic direction. Ensuring adequate resources for each project increases the probability of success of the strategy. Creative finance models, focused on maximizing spending that directly impacts learners—and in partnership with school foundations—can help support strategic direction.

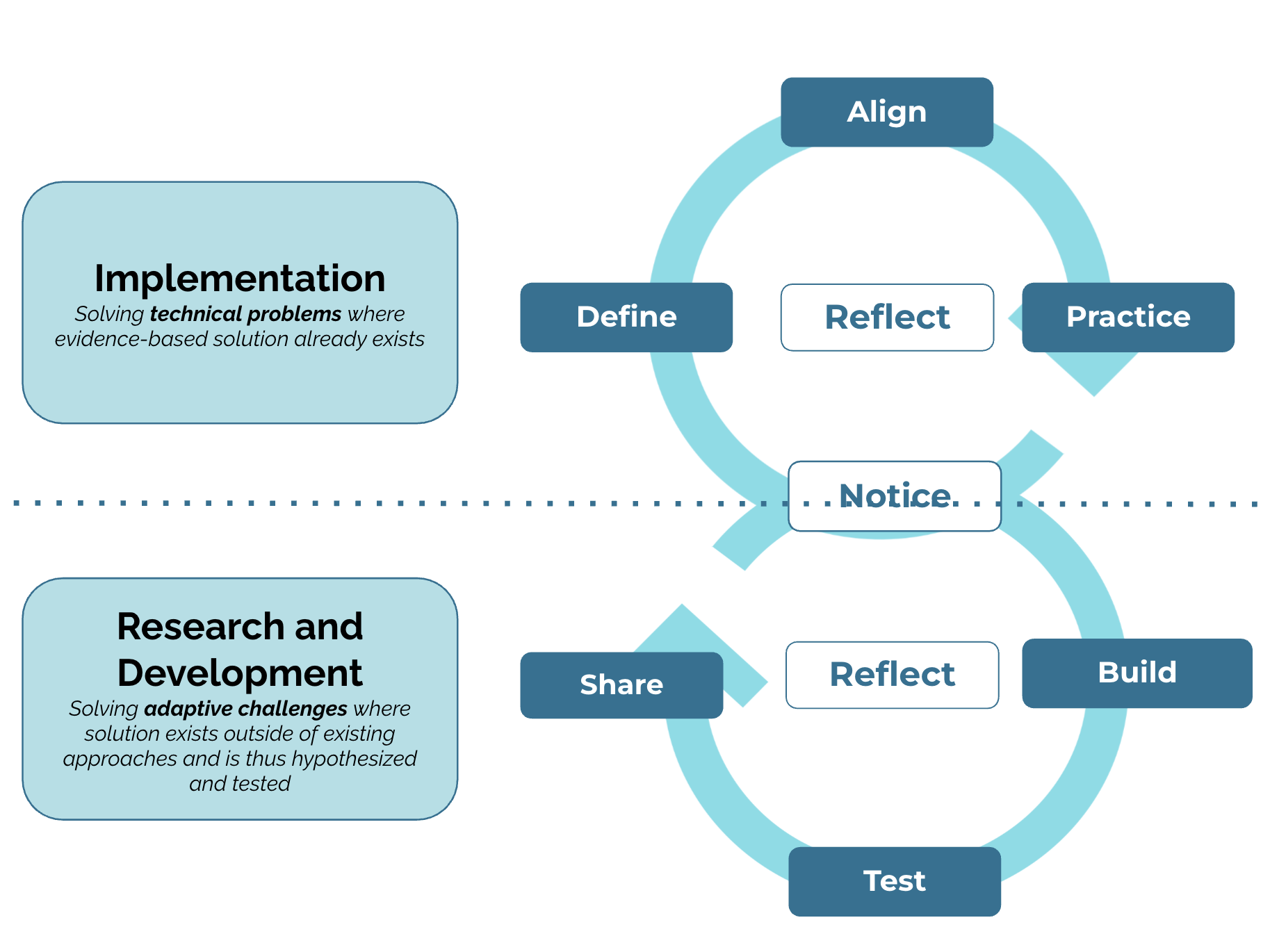

A Process for Technical Implementation

After a strategic direction has been put into place, it’s time to develop a system of implementation and continuous improvement. The difficulty lies in the varying processes and terminology used by different intermediaries and districts. Implementation Science is well-researched and articulates the process by which evidence-based practices are put into place (often consisting of exploration, installation, initial implementation, full implementation with detailed explanations and approaches for each phase). Implementation Science is used for technical challenges, where evidence-based solutions are known.

We simplify this into the following five steps:

- Notice. Observations, surveys, data, etc., all drive this phase, with the goal of clearly understanding the problem to be solved (e.g., 3rd-grade reading, high school graduation rates).

- Define. Define the evidence-based solution to be used. Ensure that the solution has a strong implementation program (or the system is willing to build the program). Build a timeline for implementation (often multi-year processes) and share the timeline with all involved stakeholders.

- Align. Align the practitioners who will implement the program. Conduct appropriate training to ensure consistent implementation with clear quality checks established prior to a pilot.

- Practice. Conduct the pilot program, collecting observations and data on the consistency and efficacy of the implementation.

- Reflect. Determine what changes are needed. Return to the Notice phase to either begin a new implementation or move to a continuous improvement cycle (see next section) to adapt to context or modifications outside of the implementation.

Without strategic alignment, implementation in learning systems is likely to fail.

Embracing Research and Development: The Power of Continuous Improvement

Most businesses allocate resources to research and development, yet this is less common in school systems. A number of states have built Innovation Zones and funds that allow for program innovation with flexibility around typical regulations that constrain districts. Some larger districts have also attempted to build innovation zones. While Denver Public Schools’ Innovation Zones have faced political pressures, New York City’s iZone has persisted, growing to include hundreds of schools investigating new models to better serve students.

The most consistent, ground-level evidence of research and development in education is the continuous improvement model. This approach is championed by organizations like the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching and is used extensively, such as through Michigan’s Integrated Continuous Improvement Process (MICIP).

At the school level, these approaches typically show up as Plan/Do/Study/Act cycles, Cycles of Inquiry, Action Research, or Design Thinking. Each focuses on various levels of practitioner agency, student perspective, and rapid iteration. We articulate the differences in the table below.

In the Learning Innovation Framework, we connect human-centered design with cycles of inquiry to create iterative design sprints for adaptive challenges (those challenges not solved by existing systems).

Stages of an R&D Design Sprint

- Notice. Similar to Implementation Science, we start with Notice. This phase provides an opportunity to gain empathy for those closest to the challenge (teachers, students, families) through data review, interviews, and observations. The goal is to build an aspiration statement and articulate a focused design question.

- Build. With a design question articulated, practitioners build a potential solution to test. The goal is to think expansively and creatively before creating an early prototype. This phase is characterized by cycles of divergent and convergent thinking.

- Test. Testing the prototype with a few different groups of students increases learning speed. Ensure clear protocols are in place to collect measurable data on the experience.

- Share. Critical to the sprint is sharing learning with others in the system – both successes and failures. Intentionally building time to discuss outcomes with other teachers and leaders in the system recognizes the importance of design sprints.

- Reflect. Decide whether to build a new solution, test the same solution, or return to the Notice phase to begin the inquiry again.

What Might a Design Sprint Look Like?

We focus on learning fast, sharing liberally, and iteration. Here are a few examples, grounded in the framework.

- Progressions. Evaluate a single criterion set in a progression around “collaboration” for a group of students on a project.

- Assessment. Have students in a single classroom set goals around 2-3 standards and progress until mastery.

- Credentials. Award students badges for clearly defined skill achievement in a tech-center classroom.

- Learning Experience. Find a local partner to test a single client-connected project for an elective class.

The integration of structured implementation (for technical challenges) and R&D approaches (for adaptive challenges) is critical. One might implement a solution that has garnered enough evidence within a set of design sprints. Alternatively, during a large-scale implementation, a particular challenge of context may emerge that requires immediate, rapid design sprints to find a local, adaptive fix.

Making R&D Stick – Critical Conditions for Success

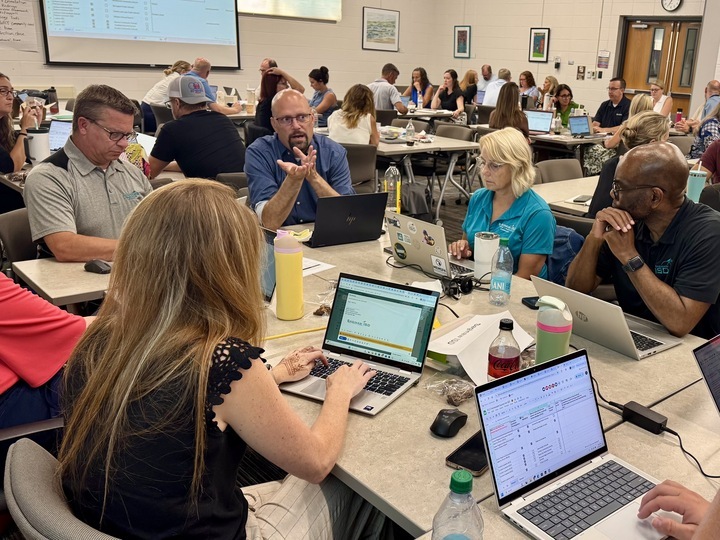

Positive Mindset & Perception: Foster a growth mindset and a positive attitude toward new technologies and innovations. Innovation flourishes when individuals perceive new ideas as useful and are open to their implementation.

Low Barriers & High Support: Innovation requires adequate time, dedicated support from leadership, and relevant professional learning. Keep barriers to entry low to encourage practitioners to adopt and master new tools and methods.

Collaborative & Integrated Approach: Encourage teacher collaboration and ensure all stakeholders have a voice. Innovations should be intentionally integrated into existing strategic direction, not treated as unsustainable add-ons, promoting a deeper and more meaningful implementation.

Teacher and Learner Empowerment & Buy-In: Actively seek and value teacher and learner voice and buy-in. When educators and students feel a sense of ownership and are part of the decision-making process, they’re more likely to champion and sustain new innovations.

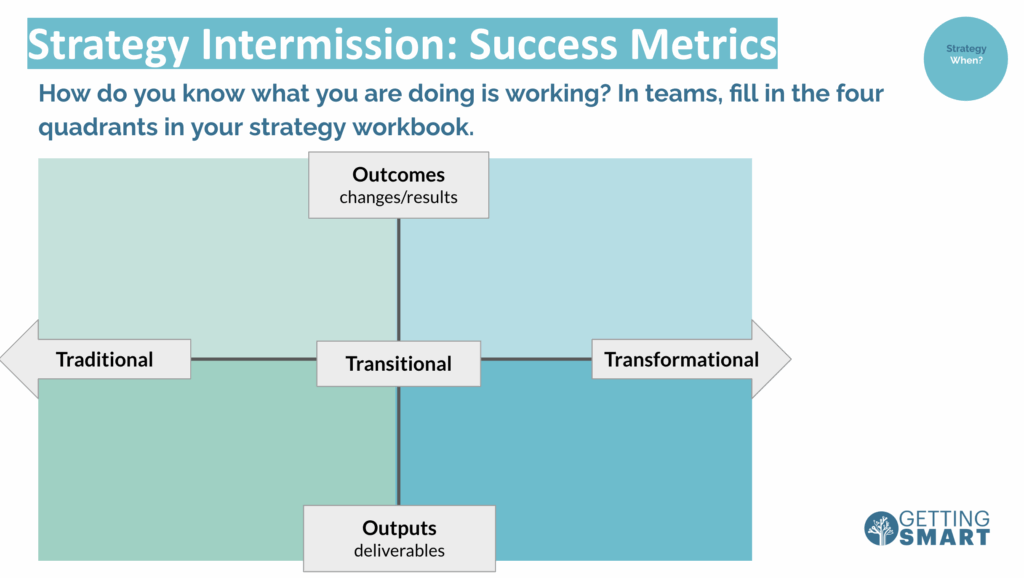

Defining Success Metrics that Matter

Within any strategic system, success metrics are the key to understanding whether the strategy is advancing. Success metrics are connected to goals within the Strategic Direction, the implementation plan, and the design sprint.

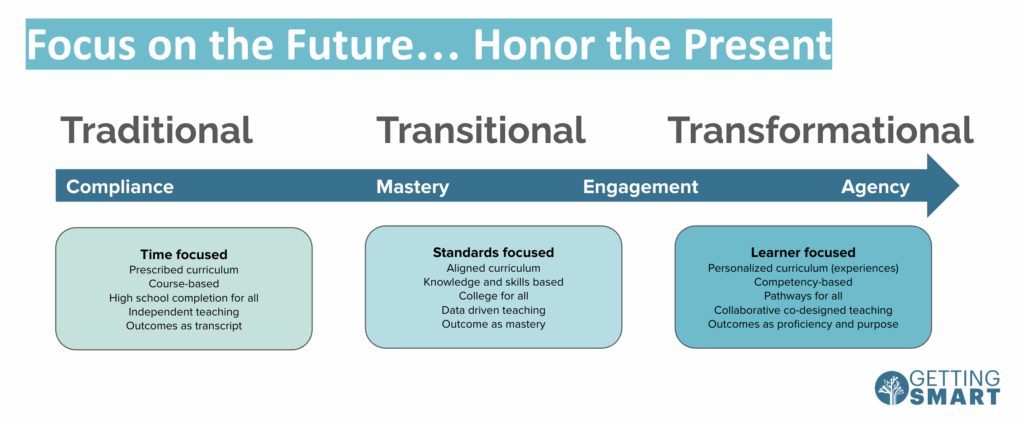

We organize success metrics using the following matrix along the continuum of system redesign: Traditional, Transitional, and Transformational (see above).

- Outputs are data that indicate the strategic effort was completed (e.g., number of participants, units covered, experiences created).

- Outcomes are data that define change in the student behavior or learning (e.g., growth in proficiency on standards, engagement changes, or sense of belonging).

Finding strong metrics that describe broader outcomes in transformational systems is an important North Star for education. We often see metrics heavily concentrated on easy-to-measure outputs or isolated short-term results (high densities of metrics in the upper left or lower right). The shift is finding metrics that genuinely capture the deeper, long-term impact of a strategic effort.

Leading Change Through Intention and Clarity

Much has been written on change management, so we simplify it to a set of guiding questions for any leader or group implementing a transformational change strategy to better serve all students.

Vision. Is there a clear vision and rationale for change? What would be different if the vision became reality?

Leadership. Do we have commitment from all major decision makers? Have they allocated the time and resources to make this change happen?

Culture. Is the culture and climate supportive of a change initiative, or is it resistant?

Community. Do we have support from the community? How will we get a continuous feedback loop with stakeholders?

Communication. Is there a clear communication plan in place to update all stakeholders?

Building a strategic learning organization takes effort, focus and adaptive leadership. However, once built, strategic learning organizations have a clear Community Vision translated into a coherent and financially supported strategic direction. This direction is then empowered by a mix of both structured implementation and research and development approaches, measured by clear success metrics.

Across the country, we see innovation efforts emerging among our partners and collaborators. Our work focuses on coalition and network building, supporting local initiatives and collective action from the ground up with tools, resources and roadmaps required to ensure every student thrives.

To support this shift, we built the Getting Smart Learning Innovation Framework as an essential organizing tool for ground-up system change, helping schools, districts and systems move toward a future vision of education that serves all students and communities. Like the education we hope for every young person, the framework is personalized and relevant, rooted in the essential questions of why, what, how, for whom and where.

Source link